The COVID-19 pandemic has strengthened corruptive forces within politics in some countries but not all.

The Spread of COVID-19 Globally: An Introduction

We all know and understand how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected our homes and daily lives, but how much do you know about how national governments worldwide have handled the pandemic? The COVID-19 pandemic has strengthened corruptive forces within politics in some countries but not all. The Philippines and Australian National government turned to corruption to attempt to remedy aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, South Korea, rather than utilizing corruptive methods, turned to more ethical ways to solve their pandemic issues. All research was produced via an institutional approach and the qualitative method to gather data.

The Philippines: The reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic was initially slow. Welfare and social aid, especially for the poor, have been hot topics of conversation as the government tackles and attempts to recover from the pandemic. “The Philippines has an estimated population of 106.7 million. The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) estimates that in 2020, six million Filipinos are senior citizens” (Vallejo 2020), adding much stress to the healthcare system that was already caught off guard by the virus since the elderly are more vulnerable to its dangerous symptoms. Initially, loose implementations were placed on The Philippines, such as the practices of “selective quarantine” of individuals who may have come into contact with the virus, keeping open any and all “international air travel” in mid- February (Vallejo 2020), which quickly tightened up come March when COVID-19 was named a growing global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) that required extensive scientific advancements as well as safety protocols across the world. Mass quarantines have been ordered by the President of The Philippines: “Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte is no stranger to authoritarian tactics, and his response to COVID-19 is no exception” (Yeo 2020). Enhanced lockdowns continue to be extended, with the impoverished people of The Philippines suffering the most, but despite little advancement at flattening the curve, Duterte “remains wildly popular” and “has support from parliament as well” in these dangerous, but politically crucial times within the dominant party system that has been created around Duterte’s regime. However, many people in opposition to him share “legitimate concerns. . . that stricter quarantine enforcement may lead to an increase in human rights abuses” (Yeo 2020) and these sentiments are correct as the virus advances. The political culture has been organized around high political trust in a strong, charismatic executive for decades and the virus response is reliant on the president. It is the institutional rules that offer the president special powers under the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act, to act as an unlimited executive: the effects of this power is trickling down to the civilian level, where much political corruption is evident during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Australia: The initial reaction and response to the Covid-19 pandemic took about two months, from Jan. 25th to March 21st. This was the first case in the country to the last day where the number of cases was the highest. Australia took early precautions to the pandemic to “flatten the curve” by “closure of international and interstate borders, local lockdown measures, physical distancing, shift to work from home, closure of non-essential businesses and full or partial closure of all schools and tertiary education facilities” (Johnson, Andrikopoulos 2020). These restrictions allowed for the number of infections to be reduced to the bare minimum. Australia has seen nearly 28,000 cases of COVID-19 and less than 1,000 deaths since December 1st, 2020. Even though the population is smaller than most countries (25 million), the citizens of Australia have come together to limit the spread of COVID-19. “The country’s response has also been characterized by effective actions, policies, and leadership practices—implemented through strong collaboration between the public and private sectors—that are transferable and repeatable elsewhere” (Child, Dillion, Erasmus, and Johnson 2020). Things are difficult during this pandemic no matter where you go in the world. It is a hard time for many people. Australia has managed to figure out ways to limit the spread of COVID-19 and every country around the world should look and see what they have done and take a page out of their playbook for this pandemic.

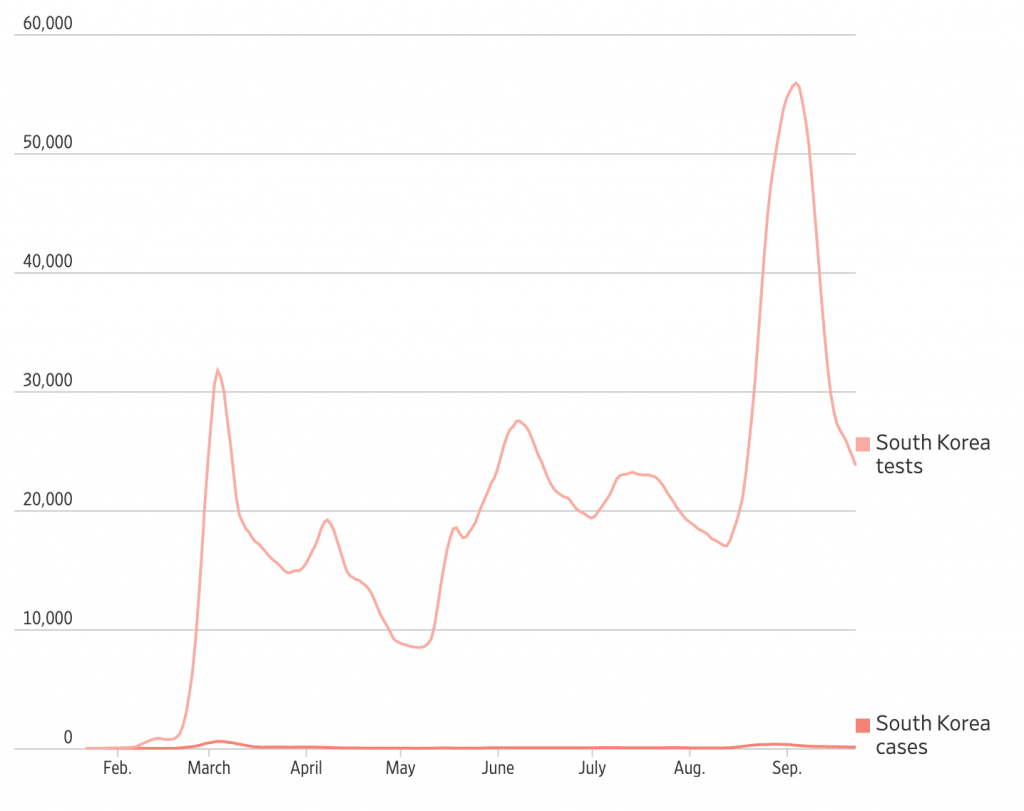

South Korea: In contrast, South Korea had a response to the COVID-19 pandemic that was one of swiftness and efficiency. The country began its response immediately, halting the transmission of the virus very early on. Due to how quickly South Korea was able to detect and tackle the pandemic, they “halted virus transmission better than any other wealthy country during the pandemic’s early months. It was about twice as effective as the U.S. and U.K. at preventing infected individuals from spreading the disease to others” (Yoon 2020). Several factors aided in their quick response. “These factors include having a well-prepared plan to respond to infectious diseases, enlisting the private sector in facilitating responses to the virus, putting a thorough contact tracing system in place, and having an adaptable healthcare system” (Medical News Today 2020). The government also established clear communication with its citizens. Due to a blending of technology and testing, centralized control, and communication (along with an added cultural fear of failure), South Korea succeeded in dwindling the cases within their borders (Yoon 2020). They began detecting COVID-19 around December, much earlier than the majority of the globe. Meetings held by higher officials were already underway. The country was prepared. “The Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare (KMHW) maintain an infectious disease plan that they update every 5 years. This plan not only details how the country should respond to an infectious disease outbreak — prioritizing the principles of openness, transparency, and democracy — but also ensures that the country has the resources and structures in place to respond to an outbreak at any time,” thus allowing the KMHW to rapidly respond to the virus. This also allowed the KMHW to detect weakness areas, lessons from past pandemics that they could improve upon (Medical News Today 2020). South Korea also “conducted rigorous and extensive epidemiologic field investigations for coronavirus cases,” supplying more and more information about the pandemic. Following the significant preparation, an aggressive amount of testing combined with stringent guidelines was instantly given. Citizens, seeing how awful the virus was affecting those of other nations, abided by the guidelines. Cooperation from the government and its people aided in the flattening of the curve. South Korea was an example to follow.

Militarization of Governments

The Philippines: Sitting at the Northern end of The Philippines is the country’s largest, most populous island, Luzon. The city was put into an Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ), widely known as one of the longest lockdowns in the world. Under the ECQ, all modes of domestic travel, including ground, air, and sea, were suspended. Residents were not allowed to leave their homes except in case of emergencies, border closures and entry bans were also enforced. Thousands of police officers and military personnel were deployed at checkpoints to ensure that people complied with the lockdown. Many families are suffering economically from this shutdown. The Social Amelioration Package (SAP) was created to provide relief but there have been reports of distribution of “no code bar and only a photocopy” which is not valid to receive aid, even to individuals who fit the criteria to receive funds, due to a quota system has been put in place that will support “just 59 percent of the total households in the city,” (Umil 2020). Local government leaders are not pleased with the quota system, although little has been done by the legislative and executive branches to reform the packages and distribution. As a unitary state, one in which sovereignty rests with the national government, regional and local units have no independent powers and are practically helpless to their constituents at this time. It is surprising that devolution has not occurred to aid local areas in such an unprecedented time. As tensions rise from many people’s financial situation, police and military are becoming more brutal towards people who are following COVID-19 guidelines. Fully armed officers are entering private residences upon reports that residents are breaching social distancing rules, “over 17,000 violators of the ECQ” have been taken into police custody, facing immediate arrest without warning (Yeo 2020). During a national speech, Duterte shared statements promoting police and military to shoot civilians, threatening to “send (violators of the ECQ) to the grave. . . don’t test the government,” (Yeo 2020). Undeclared martial law and the informal militarization of the government with the aim, stated by The Philippines’ president himself, to annihilate those in opposition to the government, is one of the many types of political corruption that have broken out during the pandemic. The military government is a violation of human rights and is highly concerning when occupying a country following a hybrid regime as this is a sign that the people in power may be interested in removing some of the more democratic aspects of the political culture that many people enjoy and replacing them with more oppressive, authoritarian ones.

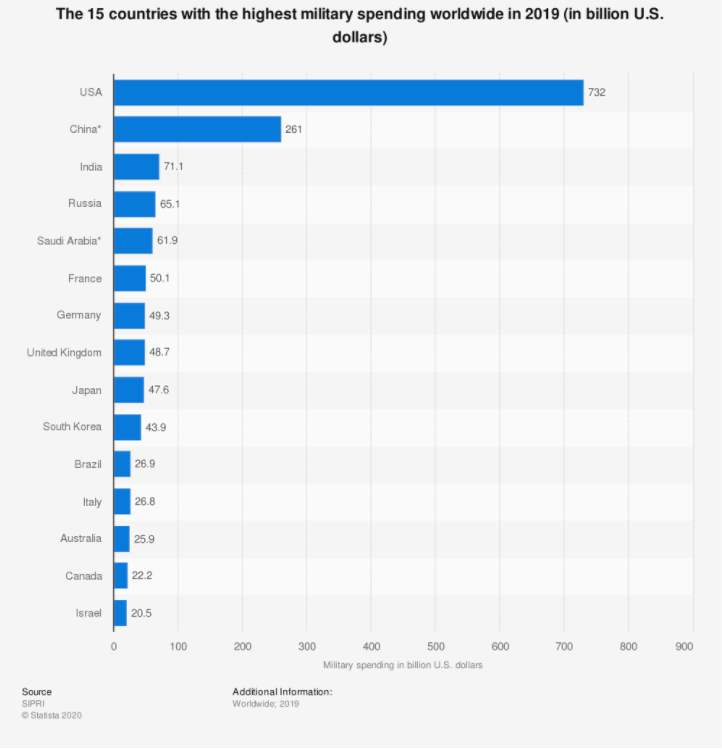

Australia: As of 2019, Australia ranks 13th in military spending worldwide, spending roughly 26 billion for military purposes, compared to the United States, which spent roughly 732 billion on the military in 2019; they are far from that. Most countries are, though. In 2019, there were corruption allegations against Australia’s Army and their main recruit facility at Kapooka. These allegations started in 2019 and continued into March 2020. As the author of the report, Andrew Greene, says there was an instance of “335,050 uncovered between what had been reported publicly on the government’s AUSTENDER website, compared to the actual expenditure as of August last year” (Greene 2020). Investigations are taking place and the Australian Defense Force (ADF) is investigating spending between May and September of 2020. In February of this year, the Australian military asked for a staggering 88 billion for new submarines, frigates, and offshore patrol vessels. These are the first corruption charges with warrants about the Australian military since 2018.

South Korea: In terms of corruption due to the pandemic itself, South Korea had little to none. The government was transparent about what they were implementing and how they were going to implement such precautions. Military rule and militarization were not present. The guidelines cite a plethora of rules and regulations to follow, including appropriate mask usage, proper distancing levels, and screening regulations. Punishments were in place for those who did not correctly follow guidelines, but no overly human rights breaking policies were set (Ministry of Health and Welfare, Coronavirus 2020). Despite the lack of human rights breaches, human rights were a concern during the pandemic’s early stages. The government had intended on compiling private information in order to track the virus. Health officials had complete access to this information and began putting out locations of those affected by the virus out publicly on government websites. A self-evident backlash met this. In response, “Local religious and civic groups have criticized South Korea’s methods as civil-rights violations and filed lawsuits. The government now offers anonymous testing and leaves out identifying information and specific names of places visited in contact-tracing disclosures” (Yoon 2020).

Along with that, the pandemic brought up an intense nationalism issue. With all the laws and regulations the South Korean government passed, lots of the population grew exceedingly worried. Was their beloved country becoming too communist? Current President Moon-Jae In is seen by those who have right-winged beliefs as too liberal. In fear of turning into the country’s northern counterpart, people revolted. Particular churches housed right-wing politicians and leaders who refused to wear masks and believed that all the action being taken by the government was a violation of their fundamental human rights (Choe Sang-Hun 2020). On the flip side, left-winged believers felt a different sense of nationalism. Many felt incredibly proud and confident in their government, glad that they could take action against COVID. This created an extreme leftist-nationalism mindset heavily broadcasted across the country (Yi & Lee 2020). This clash of nationalism on extreme sides of the political compass caused intense political issues. Questions of human rights were thrown about. Despite these incidents and the now intense political climate, South Korea had less extreme human rights issues. Those that were deemed issues were caused by questions by the citizens, questions that the government listened to in time.

Media Censorship

The Philippines: Reporters, journalists, and other researchers aiming to collect data and news on the COVID-19 pandemic within The Philippines, with the intent to share with the public, are facing very tumultuous roadblocks. The Philippines has always been a political arena that does not appreciate opposition in the form of social movements or within the media. Reporters turning up dead is not unusual. They often face different forms of legal, social, and physical violence, harassment, and threats both online and in person. However, the lack of availability of in-person harassment due to COVID-19 guidelines has caused a swell in digital activities of the sort. “Websites of news outlets have also been hacked and taken down” (Tuazon 2020) as online trolls attempt to control the voice of alternative media outlets that are not controlled by economic or political interest, who are trying to uphold the rights and responsibilities of democracy. It is these outlets of the press, who do not want everyday people to be blinded by the elite political culture who are most vulnerable to censorship. The role of the media and press is crucial during the pandemic because everyone must be informed in order to put up a united front in order to be rid of the virus. There’s an “often overlooked relationship between journalism and public health” (Bernadas 2020) and people with political power should be amplifying the sounds the press is making relating to COVID-19 to help push their own health policies and agendas, but instead, matters have been allowed to get this bad because Duterte and his followers have stood idly by as disinformation has been spread on numerous social and political topics, now including the pandemic.

Social, reinforcing cleavages that pre-existed have been magnified during the pandemic in The Philippines as many “bots” are breaching social cybersecurity at masses, producing and reproducing hate speech and false COVID-19 analytics reports (Uyheng 2020). The same groups that were targeted with hate speech, the economically disadvantaged and marginalized Muslim communities, are the same groups that have less access to proper healthcare and will be more likely to search for information elsewhere, which is part of the reason that the false information spread is a huge issue. As research was done on what was quickly becoming a “politically heated landscape” online, it was found that most of the disinformation is “primarily domestic and state-sponsored,” (Uyheng 2020). Not only is the press subject to censorship, but the state is now using the flooding of posts to stir up racial and xenophobic tensions as well as spread false information to use fear as a tool to justify exercising power. It is not coincidental that The Philippines’ national government has not supported the public press in these times, since they are trying to take hold and control of the messages seen by citizens. “Despite the availability of different studies about preventive measures in other countries, there is a significant lack of academic research addressing the COVID-19 situation in the Philippines” (Prasetyo 2020) which is both a cause and a symptom of the censorship of the free press.

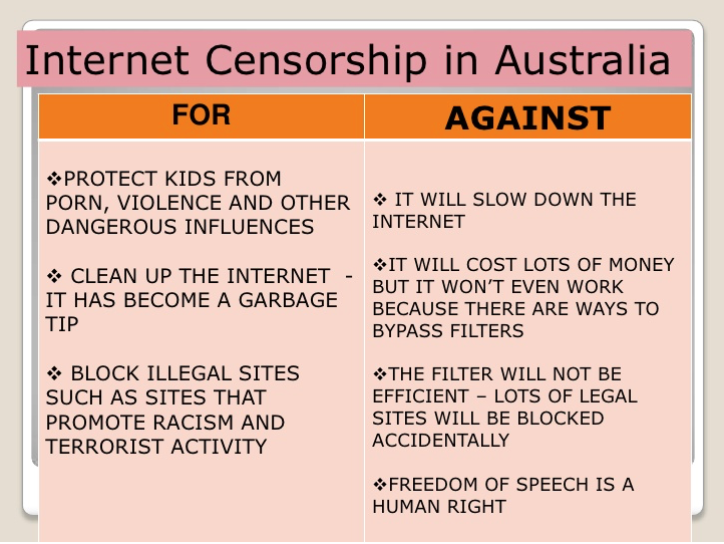

Australia: Australia is actually one of the countries with the strictest censorship laws in the world. Stated within the government website about censorship across all platforms, “Under the Constitution, the Commonwealth Government has the power to make laws with regard to telecommunications (including broadcasting) and imported material, but not locally produced matter. The latter is under the jurisdiction of the State governments. Censorship provisions have thus varied according to the nature of the material (TV, film, print etc.) and the state or territory” (Jackson 2001). The state censors the local media and the commonwealth censors the international material. In 1995, the country as a whole started to pass internet censorship laws which are very rigid. In recent times, during the COVID-19 pandemic, an Australian journalist lost his job due to a blog post. Journalist, Josh Krook, wrote an article about how big tech is taking advantage of people during the COVID-19 pandemic and making huge profits. About three months after he wrote his blog post, he was told that he had to take it down or risk losing his job and ruin his career. “His post talked only in generalities. It made no reference to any individual company and did not mention, let alone criticize, the Australian government or government policy” (Knaus 2020). Krook’s boss stated that writing about big tech companies is “risking the relationship between big tech and the government.” Josh decided not to take the blog post down, facing termination and other consequences. It is very suspicious how the government supports big tech companies but uses excuses to defend this relationship. There are many instances of censorship throughout the world especially during the pandemic; this is just another example of how censorship can really protect some and ruin others.

South Korea: South Korea utilized social media as a way to publicize and spread the word about many topics. These topics include information about COVID, social distancing laws, quarantine laws, travel laws, and other items about the pandemic. Communication was a central focal point of South Korea’s response to the pandemic. Whatever the government did, they wanted their people to know about it. South Korea implemented proposals from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), emphasizing five major communication points. The points included; be right, be first, build trust, express empathy, and promote action. In turn, “Government officials held press conferences twice a day, giving journalists the chance to ask questions. Officials also maintained various phone lines, websites, and social media channels to provide the public with up-to-date information and communicate the latest guidance” (Medical News Today 2020). The government did not want a repeat of past mistakes.

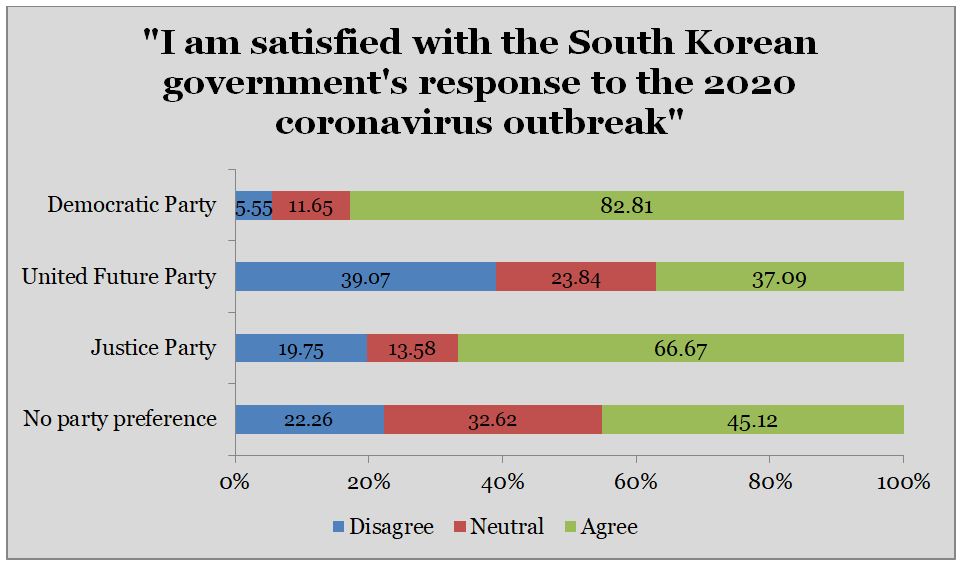

With all this information going out publicly, a plethora of concerns were raised. The content of the information being pumped out seemed to be left-leaning, almost congratulating the government for its deeds. This raised the political hostility between the right and left throughout country. Sending out information that has intentionally leaned towards a political side could be viewed as propaganda (Jo & Chang 2020). Information such as this could potentially lead to misinformation, which is glaringly awful for times like this. Other than that potential issue, communication via social media aided the country rather than harmed it. Word of the pandemic easily spread and people complied in order to solve the issue at hand. When asked about their satisfaction with the government’s response to COVID, the majority of citizens were satisfied, even despite the vast partisan issue occurring (The Diplomat 2020). Communication was utilized in a way that was to their benefit, thus aiding in their speedy recovery from the virus.

Patronage and Clientelism

The Philippines: Local Filipino politicians often want to seek out resources for their communities, as there is a congestion of money and political activity within Metro Manila but generally nowhere else. This has been an ongoing issue local governments in The Philippines have faced for many years, making them logically much more vulnerable to working at the hands of those who can offer them money and resources for their constituents. “Three Philippine journalists were killed in 2019, probably by thugs working for local politicians, who can have reporters silenced with complete impunity,” (Reporters without Borders 2020). The killing and dehumanization of journalists and the press have increased, as discussed previously, and there is quite a possibility that this could have been at the hands of vulnerable people seeking help and protection from the state in these dangerous, unprecedented times. The online bots, also previously discussed, that have become a crucial part of the socio-political COVID-19 discussion online, have also most likely spurred from technologically advanced individuals at the hands of Duterte who seek to gain money or other reimbursements. Little research has been conducted on bribery and clientelism within The Philippines, due to fear and the threat of violence, but there must be instances of it within the country due to different unsolved events that have occurred online and with the press, especially since this is a time where local leaders and their constituents may need support from the national government.

Australia: The Australian government has made it seem that they really discourage patronage for the wrong reasons. They want patrons that are there to help out the government for the common good. For example, the Australian government website states “The Governor-General will not accept invitations for patronage from professional bodies, non-incorporated entities (such as projects, scholarships, and memorials), and local organizations based outside the Australian Capital Territory.” The government wants its patrons to demonstrate “a clear focus on relevant issues and/or national interests, a significant record of achievement over at least five years, and sound financial management and strong governance arrangements.” There are over 150 companies and organizations that are royal patronages to the Australian government. These organizations and companies are either patrons to the Governor and they support the Governor-General or they are joint patrons where they support the Governor and the Commonwealth. The patrons in Australia are supporters of the Governor and/or the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth and Governor-General don’t want just anyone’s support, they’d prefer the support of organizations and companies that are supporting them for the correct reasons. In some more corrupt countries, patronage may occur for the wrong reasons: personal gain of the organization, company, or individual.

South Korea: Bribery has always been an issue within the South Korean Government. In terms of corruption, bribery has held the top spot. Many laws have been implemented in order to avoid situations involving bribery. However, in terms of COVID, no bribery issue has been outed with a clear correlation with the pandemic. There could be many reasons as to why. There was an enormous public eye on the government due to the pandemic. Any action taken by almost any official would be dissected and discussed. People had to be careful. The pandemic also rendered people to stay home. Doing most things at home, whether it be schoolwork or money laundering, is difficult. South Korea was able to escape the grips of bribery, for now. Time can only tell what can happen next.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic put many national governments to the test as far as how to handle spreading cases, create health protocol and policies, and flatten the curve. The Philippines and Australian National government chose to handle the pandemic with acts of corruption in the form of militarization, censorship of press, and patronage whereas South Korea took action to utilize cooperation from both the government and the citizens to resolve the pandemic as a whole, setting guidelines and regulations for all of the country to follow. There is lots of predictability in how these countries will handle a second wave of the COVID-19 virus or another future pandemic based on the findings. Citizens should not turn a blind eye to these types of corruption, and hopefully the data can provide a more clear view of the realities of varying governments’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects on politics.

References –

Bernadas, Jan Michael Alexandre C, and Karol Ilagan. “Journalism, Public Health, and COVID-19: Some Preliminary Insights from the Philippines.” Media International Australia, vol. 177, no. 1, 2020, pp. 132–138., doi:10.1177/1329878×20953854.

Prasetyo, Yogi Tri, et al. “Factors Affecting Perceived Effectiveness of COVID-19 Prevention Measures among Filipinos during Enhanced Community Quarantine in Luzon, Philippines: Integrating Protection Motivation Theory and Extended Theory of Planned Behavior.” International Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 99, 2020, pp. 312–323., doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.07.074.

Reporters without Borders. 2020. “2020 World Press Freedom Index.” Accessed on Dec. 19, 2020. https://rsf.org/en/ranking (Links to an external site.).

Tuazon, Ramon R., and Therese Patricia San Diego Torres. “Digital Threats and Attacks on the Philippine Alternative Press: Range, Responses, and Remedies.” IGI Global, IGI Global, 1 Jan. 2020, www.igi-global.com/chapter/digital-threats-and-attacks-on-the-philippine-alternative-press/246424.

Umil, Anne Marxze, et al. “Social Amelioration Program, Inadequate, Slow.” Bulatlat, 17 Apr. 2020, www.bulatlat.com/2020/04/17/social-amelioration-program-inadequate-slow/.

Uyheng, Joshua, and Kathleen M. Carley. “Bots and Online Hate during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Case Studies in the United States and the Philippines.” Journal of Computational Social Science, vol. 3, no. 2, 2020, pp. 445–468., doi:10.1007/s42001-020-00087-4.

Vallejo, Benjamin M., and Rodrigo Angelo C. Ong. “Policy Responses and Government Science Advice for the COVID 19 Pandemic in the Philippines: January to April 2020.” Progress in Disaster Science, vol. 7, 2020, p. 100115., doi:10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100115.

Yeo, Andrew. “The Militarization of COVID-19 Enforcement: Observations from the Philippines.” Duck of Minerva -. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://duckofminerva.com/2020/04/the-militarization-of-covid-19-enforcement-observations-from-the-philippines.html.

“Patronage Listing.” Governor of New South Wales. Her Excellency the Honourable Margaret Beazley AC QC, 2020, www.governor.nsw.gov.au/governor/patronages/patronage-listing/.

Knaus, Christopher. “Australian Public Servant Condemns Censorship after Blogpost Cost Him His Job.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 23 Aug. 2020, www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/aug/24/australian-public-servant-condemns-censorship-after-blogpost-cost-him-his-job.

“Censorship and Classification in Australia.” Home – Parliament of Australia, CorporateName=Commonwealth Parliament; Address=Parliament House, Canberra, ACT, 2600; Contact=+61 2 6277 7111, 18 Feb. 2013, www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/Publications_Archive/archive/censorshipebrief.

Greene, Andrew. “Army’s Kapooka Training Base Hit by Fraud and Corruption Allegations.” ABC News, ABC News, 5 Oct. 2020, www.abc.net.au/news/2020-10-04/kapooka-corruption-allegations/12727280.

Department, Published by Statista Research, and Dec 1. “Ranking: Military Spending by Country 2019.” Statista, 1 Dec. 2020, www.statista.com/statistics/262742/countries-with-the-highest-military-spending/.

Douglas, Chris. “Corruption Threatens Australia’s Defense Program.” – The Diplomat, For The Diplomat, 12 Feb. 2018, thediplomat.com/2018/02/corruption-threatens-australias-defense-program/.

Child, Jenny, et al. “Collaboration in Crisis: Reflecting on Australia’s COVID-19 Response.” McKinsey & Company, McKinsey & Company, 15 Dec. 2020, www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/collaboration-in-crisis-reflecting-on-australias-covid-19-response.

Andrikopoulos, Sof, and Greg Johnson. “The Australian Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic and Diabetes – Lessons Learned.” Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, Elsevier B.V., July 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7266597/.

Australian Government Department of Health. “Government Response to the COVID-19 Outbreak.” Australian Government Department of Health, Australian Government Department of Health, 28 Aug. 2020, www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/government-response-to-the-covid-19-outbreak.

Jo, Wonkwang, and Dukjin Chang. “Political Consequences of COVID-19 and Media Framing in South Korea.” Frontiers. Frontiers, July 14, 2020. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00425/full.

Martin, Timothy W., and Dasl Yoon. “How South Korea Successfully Managed Coronavirus.” The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, September 25, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/lessons-from-south-korea-on-how-to-manage-covid-11601044329.

Ministry of Health and Welfare, Coronavirus disease 19(COVID-19). “Coronavirus Disease-19, Republic of Korea(COVID-19).” Coronavirus disease 19(COVID-19). Accessed December 21, 2020. http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en/guidelineView.do?brdId=18.

Rich, Timothy S. “What Do South Koreans Think of Their Government’s COVID-19 Response?” – The Diplomat. for The Diplomat, October 8, 2020. https://thediplomat.com/2020/10/what-do-south-koreans-think-of-their-governments-covid-19-response/.

Sang-hun, Choe. “In South Korea’s New Covid-19 Outbreak, Religion and Politics Collide.” The New York Times. The New York Times, August 20, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/20/world/asia/coronavirus-south-korea-church-sarang-jeil.html.

“What the Rest of the World Can Learn from South Korea’s COVID-19 Response.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, August 10, 2020. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/08/200810141006.htm.

Yi, Joseph, and Wondong Lee. “Pandemic Nationalism in South Korea.” Society. Springer US, July 17, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7367163/.

Contributors

Alexis Savoie is a Political Science major with an expected graduation date of May 2024.

Riddhi Patel is an Undecided major with an expected graduation date of May 2024.

Matthew Doran is a Communications major with an expected graduation date of May 2022.