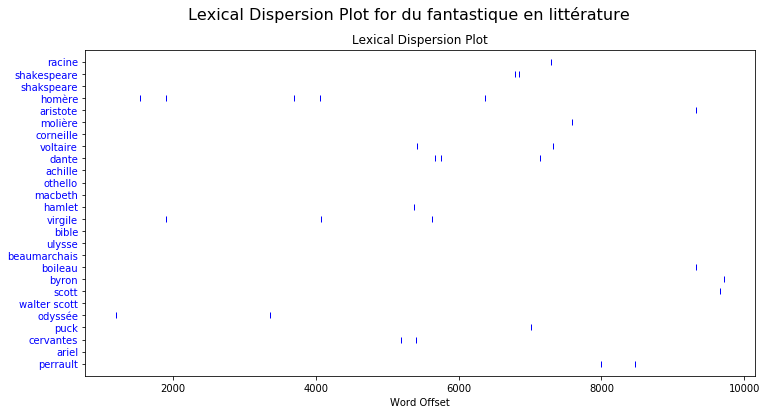

A timeline of the romantique and classique debate in France and England from 1813 to 1830.

Much of the romantique contre classique debate pitted an energetic, passionate and original Shakespeare against a flat, dull and unoriginal Racine. Irish novelist Sydney Owenson, Lady Morgan launched the first sally in her study of France during the early years of the Bourbon Restoration.

Sydney, Lady Morgan. “French Theater,”France. Vol 1. M. Thomas, 1817, Philadelphia.

“Racine produced elegant paraphrases of the Greek dramas; adhering strictly to their rules and unities, but violating the propriety of action in every scene, by blending the formal frivolity of the French manners, with the grand solemnity of antique fable” (64).

“But Racine, though an historian, was not a philosopher, in any sense of the word: and it would be vain to search, in his correct pages, for one of the thousand citations referable to every point of human conduct and human feeling, which Shakespeare presents as the reading illustrations of every text in the moral existence of man” (65).

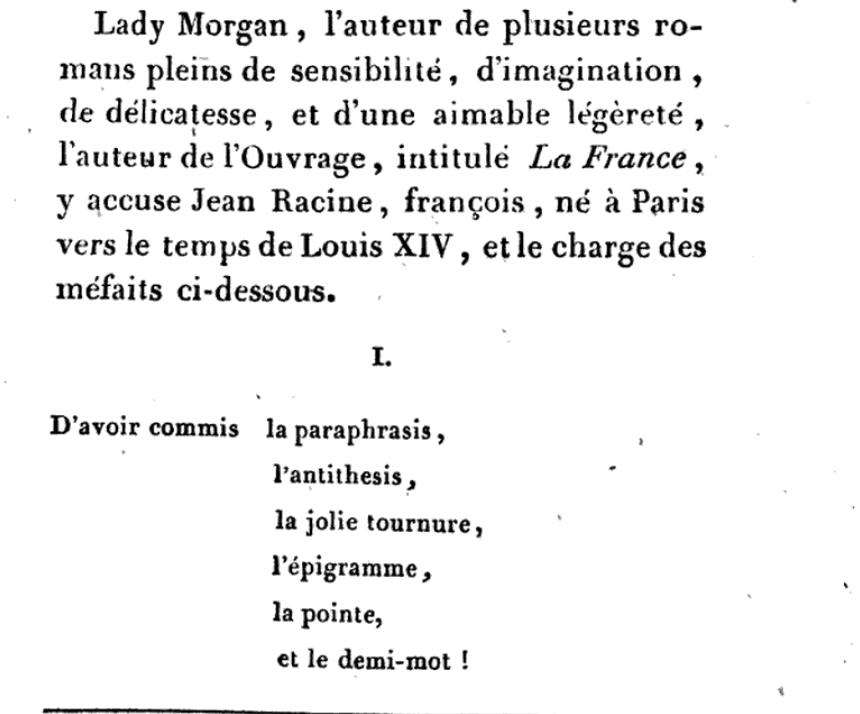

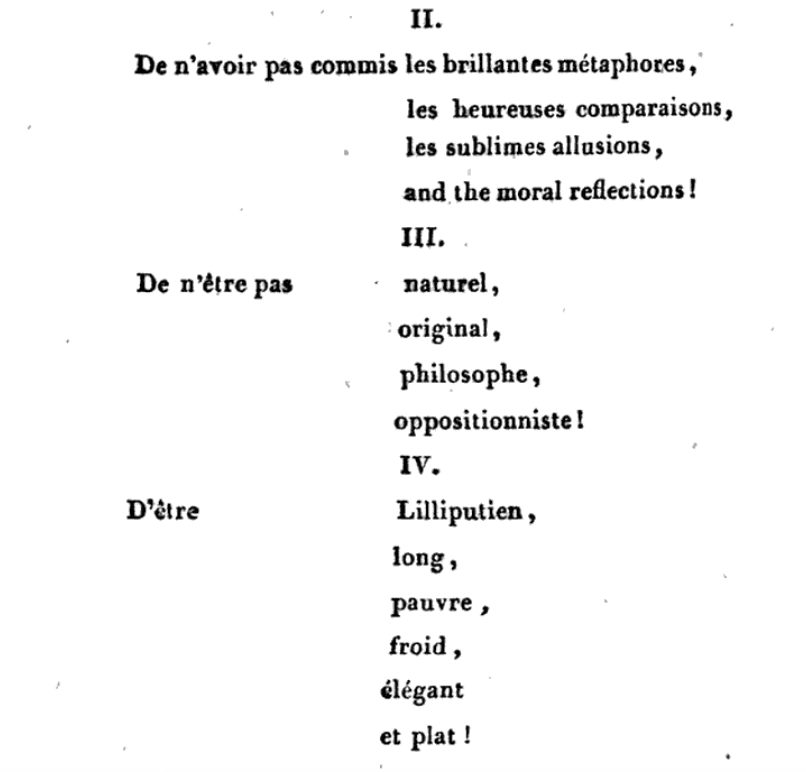

The following year, Charles Dupin responds to Lady Morgan with Lettre à MyLady Morgan sur Racine et Shakespeare. Dupin writes to defend Racine against what he sees as Lady Morgan’s slanderous attack against French literature. Another source of outrage against France may well be that Lady Morgan asserts, surreptitiously, in a footnote, that there’s no way Voltaire actually understood Shakespeare and that his translations of the plays are “ill executed” and “his attempts at a version are, indeed, little more than burlesque parodies” (63). The final section of Dupin’s book begins with a list of Lady Morgan’s accusations against Racine, which she discusses in Book VII of France. Within the context of the Restoration and the continued debate between romantique and classique, the list reads as a cheat sheet for Nodier, Stedhal, Hugo, Henri de Latouche, Alexandre Guiraud and other writers who took up the cause of defending the romantiques against the classiques.

Notably, in his 1821 review of Le Petit Pierre, Henri de Latouche’s French translation of a German Gothic novel, Charles Nodier will build on criticisms similar to those that Lady Morgan outlined in 1817, and he will add in the charge that Racine isn’t really a French poet.

Racine n’est pas un poète national; c’est un poète grec, un poète hébreu, qui a la touchante éloquence d’Euripide, la majesté sublime d’Isaïe. Je trouve tout en lui, excepté ce que le coeur d’un français demande à son poète, le chant de la patrie, avec les nobles traditions de nos chroniques et les mensonges enchanteurs de nos fables.

Nodier, Charles. “Le Petit Pierre, traduit de l’allemand, de Spiess” Le Petit Pierre, Christian Heinrich Spiess, Translated by Henri de Latouche, Éditions Cartouche, 2005, Paris.

Nodier conjectures that had Schiller been born in France, he would have given French literature the originality and independence it needed to distinguish itself from classical literature. Nodier mentions Shakespeare in the context of romantiques forging a connection to the people of their day and their national history.

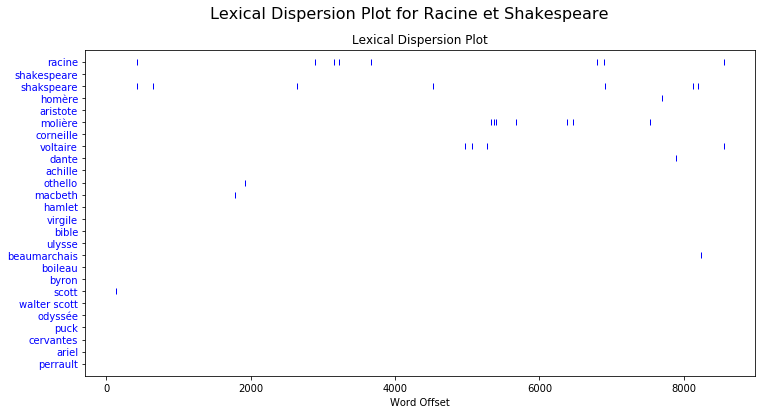

This question of nationalism as it relates to romantique contre classique was certainly on Stendhal’s mind in 1822 when he wrote the first part of Racine et Shakespeare for the October edition of the Paris Monthly Review. In July of that year, a troupe of English actors were unable to successfully stage Othello because a raucous and hostile audience drowned out their words. It’s French patriotism, Stendhal writes, that prompted the audience to boo Shakespeare because the bard was English. But really, Stendhal continues, the beef between Racine and Shakespeare isn’t one of nationality.

Toute la dispute entre Racine et Shakspeare [sic] se réduit à savoir si, en observant les deux unités de lieu et de temps, on peut faire des pièces qui intéressent vivement des spectateurs du dix-neuvième siècle, des pièces qui les fassent pleurer et frémir, ou, en d’autres termes, qui leur donnent des plaisirs dramatiques, au lieu des plaisirs épiques qui nous font courir à la cinquantième représentation du Paria ou de Régulus.

Stendhal. Racine et Shakespeare. Le Divan, 1928, Paris.

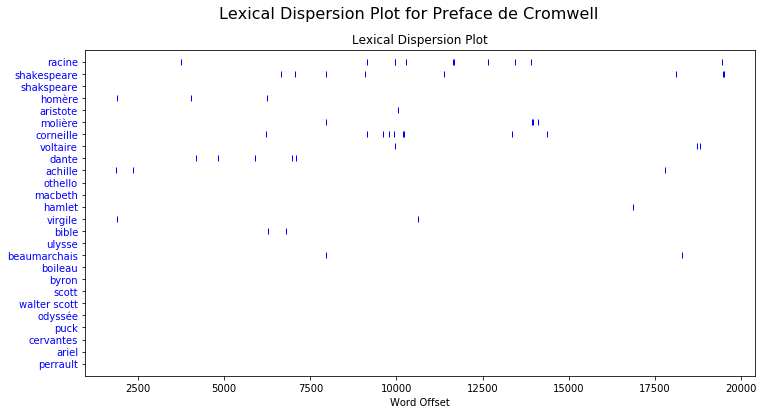

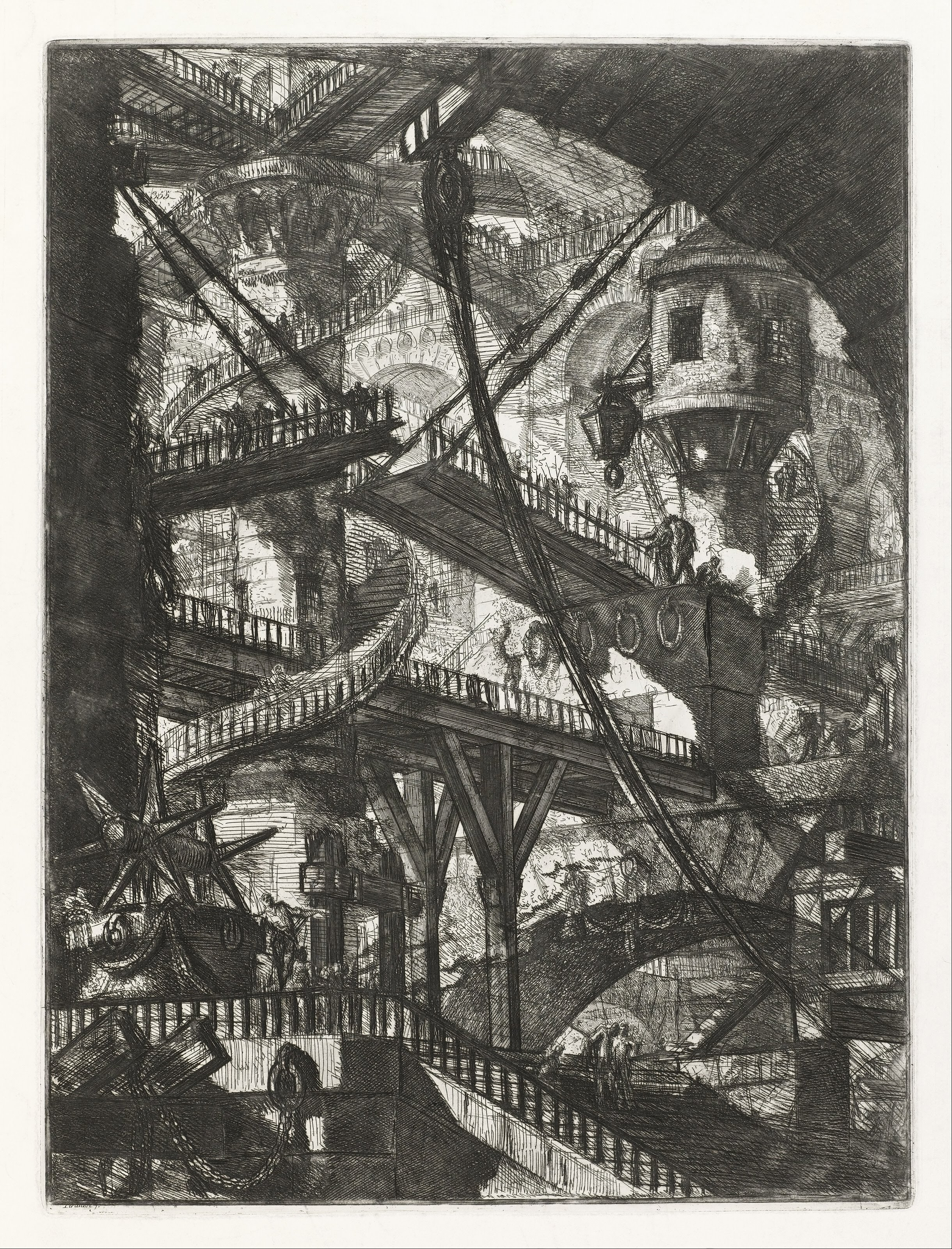

Regardless of Stendhal’s focus on dramatic conventions, in the first decade of the Restoration, the romantique contre classique debate had nationalistic undertones. The partisans of of the romantiques claimed that the classiques did not write a national literature and did not speak to the French people the way that Shakespeare, Byron, Scott, Goethe and Schiller spoke to their people. In 1824 académicien Simon Auger, in his speech before the Académie Française, Discours sur le romantisme, warns against “l’atmosphère brumeuse de la Grande-Bretagne ou de la Germanie.” Auger even questions Madame de Staël‘s national sympathies in his speech.

Cependant, à une époque plus rapprochée de nous, une femme justement célèbre, toute française par ses sentiments, ses affections et ses goûts, mais que les vicissitudes de sa destinée avaient rendue cosmopolite, rapporta d’une de ses plus longues excursions le système germanique, nous en apprit le nom en même temps que les principes, et nous révéla la fameuse distinction de classique et de romantique, qui divisait, à leur insu, toutes les littératures et partageait la nôtre même , qui ne s’en serait jamais doutée. Son exposé, où la prévention se cachait mal sous un air d’impartialité, fut, pendant quelque temps, l’objet d’une controverse que fit taire bientôt le fracas des événements et des intérêts politiques.

Auger, Louis-Simon. Discours sur le romantisme prononcé dans la séance annuelle des quatre académies du 24 avril 1824. Firmin Didot, 1824, Paris.

Auger’s speech takes us back to the beginning of the romantique contre classique timeline: Mme. de Staël’s De l’Allemagne. In the chapter on classical poetry and romantic poetry, she notes that the France, in its status as “la plus cultivée des nations latines,” prefers poetry imitated from classical style, while England, “la plus illustre des nations germaniques,” prefers romantic and chevaleresque poetry (162). There is, as she puts it, “la diversité des goûts.” And those tastes are developed by a variety of factors.

I will leave the question of taste for another time.