Background and Origin of Cajun Mardi Gras

Cajun Mardi Gras or the Cajun Courir de Mardi Gras “professional begging ritual” in Southern Louisiana incorporates both parody and tradition (Lindahl, 57). Held on the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday, this celebration is similar to early begging rituals. The celebration involves eating and drinking heavily, dressing in costumes, and wearing masks to protect identities during parades and dances. To briefly describe the festival, it is typically young men and boys who disguise themselves in costumes so that neither friends nor family can recognize them (Lindahl, 58). They are under the supervision of the main leader, or Capitaine, and co-Capitaines (see featured image); these Capitaines are the only ones unmasked (Lindahl, 58). The group travels together from the center villages to rural farms in cycles with the main goal of coaxing livestock from farmers, especially chickens to be used in gumbo (see fig. 2) later that night at the bal masqué, or dance (Lindahl, 58). The Capitaine first asks the farmer or host of the troupe whether the troupe can enter his property; the process then starts when the farmer releases livestock and the troupe must capture it (Lindahl, 58). Cajun Mardi Gras incorporates many aspects of opposites, with creativity and tradition rivaling each other, and respectability versus entertainment going head-to-head, in addition to others. Cajun country can be separated into Creole and African American populations, in which Mardi Gras combines both Afro-Caribbean and French Louisiana Mardi Gras elements (Gaudet, 154). This festival is still practiced by two dozen rural communities. Cajun Mardi Gras is “ambivalent” in which the festival both wreaks havoc on the town, yet it reestablishes the roots when finished (Lindahl, 60). Lindahl describes how Mardi Gras “transforms everything and everyone” (61). While the Cajun Mardi Gras and subdivisions of the tradition are meant to be a traditional festival involving fun and excitement, the Cajun Mardi Gras seems to juxtapose the very bases of society; through decorative masks and carefully created costumes, participants can challenge societal rules, but at the same time solidify those very same rules.

Fig. 2. Maskers capture livestock; here the traditional chicken is being captured (Lindahl, 59).

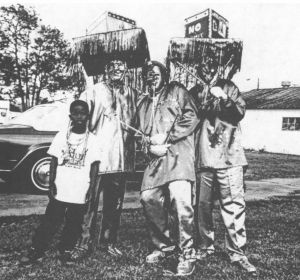

The main goal of Cajun Mardi Gras is the creation and support of a community and a sense of unity. Additionally, there is a creation of group territory due to the cyclical nature of leaving from the center of town to rural outskirts and back (Lindahl, 58). This cycling leaves a trail of horse hoofs, which leave boundary marks. The festival also serves as an important turning point in the young man’s life, almost a coming out to society for young boys, by defining manhood (Lindahl, 59). However, those too young to participate just assume the role of an audience member even if their family members are eligible to participate (see fig. 3). Mardi Gras “defines the vitality and promotes the continuity of the group” where young men mingle with the older male role-models and participate in the courting of females at the bal masqué (Lindahl, 59). Generally, the procession originated to be for all males, however, women have become increasingly part of this tradition. Some of the main skills learned and taught during the festival include “horsemanship, resourceful farming, prowess at racing and dancing, hard work, hard play—all combined” (Lindahl, 59). The boy who proves himself well through play or is first to catch the chicken becomes an official man (Lindahl, 59). There is a sense of interdependence in the community due to the anonymity of masked individuals who can be extremely different from the person next to them without knowing (Lindahl, 59). A sense of community is created by providing an outlet for expression, especially through creativity and freedom of mask and costume creation.

Fig. 3. Maskers posing with a child of one of the maskers who is not yet old enough to participate in the festival (Gaudet, 158).

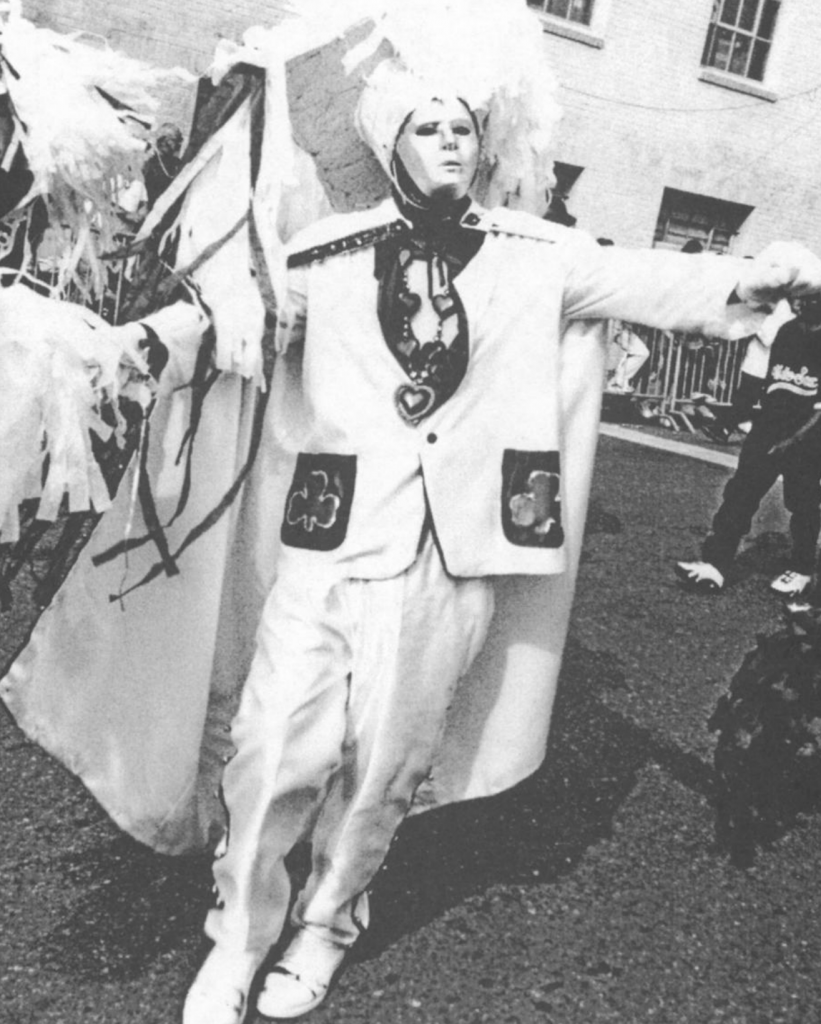

The most traditional Mardi Gras masks are usually described as being wire screen masks. Costumes often include a pointed hat called “capuchon” and a colorful two-piece suit (Ware, 226). Although the traditional masks are most preferred, individuals have chosen to modernize the custom even using comedic reliefs (see fig. 4); disguises can resemble clowns, monsters, Halloween creatures, and cartoon characters (Ware, 226). The clothing is usually made from cotton or “synthetic blends, cut on a pajama pattern” (Ware, 229). Not only does the festival juxtapose elements of tradition and society, but the costumes physically juxtapose prints with bold colors like yellow, green, and hot pink (Ware, 229). Differing from the more mainstream Mardi Gras in Louisiana consisting of mainly purples and greens and simpler masks (see fig. 5) Cajun Mardi Gras is more unique and traditional. The most popular masks are wire-screen masks, but those such as Tee Mamou women have incorporated the use of needlepoint masks on plastic mesh (Ware, 230). Additionally, most cover the entire face, and even extend above and below for maximum coverage of disguise (see fig. 6); some even extend twenty inches above the head (Ware, 230-231). Needlepoint has become accepted because it is often more comfortable than wire masks that can cut participants during chaos and movement. In addition to the production of masks, creativity comes from the choices of individuals to include three-dimensional pieces such as costume jewelry, streamers that trail behind when walking (see fig. 7), or even tire treads (Ware, 230). Masks are supposed to be distorted and disproportionate (Ware, 230). Masks are brought to another level at the night ball, where individuals often incorporate sequins or flashing lights (Ware, 230). Rewards are even given to the prettiest and ugliest masks (Ware, 231). Women will often pair their costumes with accessories like wigs or sombreros, or some will pair costumes with another individual to match, which magnifies anonymity and confusion of the audience even more (Ware, 232). Masks are thought of all year round, with individuals picking up small pieces from other masks or items here and there to save up for the big day (Ware, 233). Truly, this festival requires dedication and passion, but there is some depth behind the themes and aspects of the festival.

Fig. 7. A more modern festival due to lack of horse riding; here it is evident the creativity maskers put into costumes and masks such as large streamers (Gaudet, 160).

Fig. 4. A non-traditional masker wearing more of a comedic mask, making fun of Jimmy Carter(Lindahl, 60).

Fig. 5. A masker that seems to resemble more of the stereotypical Louisiana Mardi Gras practiced by many Americans today (Gaudet, 159).

Fig. 6. Masker wearing the traditional large mortar-board hat (Gaudet, 157).

The Opposing Forces

Respectability and entertainment are two of the main goals of Cajun Mardi Gras, yet these seem to be opposing forces in everyday life. For example, costumes for Halloween usually have no limits, and no conscious efforts to respect boundaries and modesty, simply to serve as entertainment. However, Cajun Mardi Gras is an outlet for representing both of these areas. Although Mardi Gras serves to provide entertainment to both the actors and audience, the actors still manage to establish their roles apart from the acted-upon by trying to settle scores or invoke revenge, even threatening those for the sake of it (Lindahl, 61). This is so riders elicit a dominant role and in turn a degree of respectability from the audience. Respect is also emitted from age, where older riders have more respect given to them and they have the role of teacher to inspire younger riders (Lindahl, 62). Going along with the idea of the duality of formality and informality, Cajun Mardi Gras contains both personal creativity and the following of traditions. The tradition allows for the creativity of costuming with masks and full-body costumes, and even farmers are allowed to spice up the competition by releasing distracting livestock like guinea hens (Lindahl, 60). Therefore, while the festival’s goals and traditions are being met, individuals add their own sense of creativity to liven the festival and make it more diverse. The main importance of the mask is the freedom that is allowed. Since identities are disguised for the day, individuals are free to create the most ridiculous costume (see fig. 8) and never fear being judged (Lindahl, 60). While Cajun Mardi Gras can be lighthearted and fun, there are unspoken rules and “behavioral precepts” that riders follow even without orders from the Capitaine (Lindahl, 62). In fact, Lindahl claims that the most creative and free times are those that are the “most ordered and constrained” (62). Cajun Mardi Gras powerfully and successfully “inverts, but does not subvert, the power structure that it mocks” (Lindahl, 62). Additionally, although disorder and metaphorical destruction of the established order is the main component of Mardi Gras, Mardi Gras, in turn, creates a “folk-centered sense of order” (Lindahl, 67). Yet, order seems to stem from the choice of chaos and creativity, individuals still differ in their decision on how to spend the day. Some individuals maintain disguise and never falter from it, and others are less strict and have fewer concealing costumes than what tradition calls for for the sake of creativity (Sawin, 182). So, while some may lack tradition, the creativity that is inspired repairs this fault and in turn reinforces the tradition.

Furthermore, individuality and tradition are also morphed into freedom versus hierarchy; while masks provide positive freedom, they also solidify social rankings. There is such a complexity in this festival, in which riders and farmers engage in “cat-and-mouse games” to see who will be victorious, further solidifying their social roles (Lindahl, 61). Even among riders, there is an uncommunicated hierarchical understanding between young and old members where riders take part in mini-wars that “playfully toils” with real-life tensions and aggressions in the group (Lindahl, 61). So, while participants are there to work as a team, it is still made clear who is in charge and who is not (see fig. 9). Maskers and non-maskers have separate benefits, where maskers have the freedom and right to ride horses and wagons and get access to free food and beers (Lindahl, 62). This freedom simultaneously creates unspoken rules in which for the day, maskers are more powerful than non-maskers; non-maskers are simply observers and witnesses, where maskers are the actors and doers. Additionally, although maskers are allowed to ride on the property of farmers, they must follow Capitaine’s orders and ask for permission from the farmer (Lindahl, 62). Then, the riders have the freedom to chase livestock and emit all sorts of various techniques. Essentially, there is a pecking order established between riders, and awards are even given out at the end of the night to superior riders, further solidifying a stepwise social order (Lindahl, 62). Additionally, the more fun or more game type behavior that occurs includes the switching of roles, where “average farmers become the center of power and where boys who will become farmers struggle to show their competence as providers” (Lindahl, 66). Lindahl describes that the festival serves as a “declaration of freedom, but a controlled tension between the poles of rule and riot” (Lindahl, 67). Masks serve as the outlet for individuality so that while freedom can occur, the order is also established.

Fig. 8. Chic-a-la-pie Mardi Gras participant adorned with an intricate and shiny costume(Gaudet, 155).

Fig. 9. The Capitaine expressing his dominance and authority over the masker (Lindahl, 64).

The Not So Good Side

Perhaps more shocking, leaning towards the darker side of the festival, the issue of gender roles is very apparent. To begin, women have been sheltered from participating as maskers in the festivals. In the past, it was only male riders and maskers, and females were only allowed to watch and dance with masked men at the night masqué (Lindahl, 61). A reason for being solely a male-run festival was to present males an opportunity to socialize (Lindahl, 64). Even expanding further, the most dangerous male delinquent catches the most chicken, yet his violence is rewarded by being named the best provider and given a trophy (Lindahl, 64). Where the festival award ceremony establishes the fact that the “most dangerous individuals” are chosen for the “most responsible roles,” wherein the real world this would not be the case (Lindahl, 64). Once women were accepted to be involved, a specific group of women, the Tee Mamou, took disguising themselves so seriously that they were often rougher than men. Perhaps they were making up for last time, or they were challenging gender roles, but it is important to realize that women began to participate seriously in the festival. Sawin suggests this is because “‘guise of temporary strangers [makes them] free to act in ways which are unpredictable” that go against conventional female roles in society (180). However, women do keep some of their stereotypical tendencies of caregiving, where they tend to be more comforting towards the audience than men, in which some take their masks off to comfort crying children scared of the chaos (Sawin, 180). The women do this by inviting them to playful dances or handing out candy. However, males and females often morph into one during the festival, since disguises can be similar and interchangeable, so it is the expression of action that distinguishes the individual (Ware, 228). Maybe more work, or simply just for enjoyment, women have an additional task, in which they change into different costumes before going to the afternoon gumbo to not be recognized by the riders they were among that day (Ware, 230). This begs the question as to why men do not have to also change costumes. Perhaps the men feel threatened by the women since occasionally women could be seen as more powerful maskers regarding the message they want to get across. For instance, some women choose to dress androgynously to be more powerful (Ware, 242). Also, women choose to dress as younger or older women as a “replay of past identities and a comic rehearsal of future ones” (Ware, 242). Therefore, women seem to have overtaken the tradition through behind-the-scenes production, creativity, and involvement becoming the public face of Cajun Mardi Gras (Ware, 244). Yet men still find the need to establish a dominant role in the festival.

There is a clear difference between the presentation of entertainment by men and women, where men tend to be cruder than women even if portraying the same character. Males often cross-dress as their costume for the run, with wigs, dresses, and lipstick, yet crudely emphasize the sexuality of women by creating large breasts, hips, and kissing audience members (Ware, 234). Another crude aspect of the festival is the creation of fabric genitals, which are concealed under a flap and revealed in the presence of adults, not children (Ware, 240). Here, there is an element to the chaos and unfiltered aspect of the festival, in addition to wild-like features.

Male cross-dressers while they serve to make fun of femininity, are subsequently reinforcing their masculinity and further diverging themselves from their role due to the comedic effect (Ware, 241). Perhaps this plays into the toxic masculinity so present in society today in which a man must not engage in any aspect of female perceived actions or else his manhood is damaged, which is why some choose to make fun of femininity during the festival.

However, it is important to note that while some invert gender roles, others reinforce gender roles (Ware, 234). Women sometimes choose to accentuate their femininity, by dressing as voodoo queens or dolls (Ware, 236). Differing, women also cross-dress, but do not act exaggeratedly; rather, they “de-emphasize sexuality” and diverge from feminine ideals (Ware, 242). Women seem to have a more sophisticated role in the festival besides having fun. While women run in Mardi Gras most recently, they also have a role in sewing and designing costumes (Ware, 225). Some of the most prolific creators include Georgie Manuel, Susan Lainey, and Jackie Miller (Ware, 225). Costumes and masks designed by women are also worn by men and children. By being at the forefront of design, women can use their creative expression to form “cultural commentary” to go with or go against social norms (Ware, 225). In the end, it is all about the freedom of individual choice, but the following of cultural norms.

Fig. 10. A masker taunting and involving the audience, threatening to drop this woman on the ground(Lindahl, 61).

A major part of Mardi Gras is that of audience participation, or in this case forceful engagement (see fig. 10). Riders often “force men and women to dance, lift them off the ground, abduct them for a few moments, or set them on the backs of skittish horses” (Lindahl, 61). Male maskers often seek “battles” with other groups of maskers, but they also aim to scare little kids (Gaudet, 154). However, this terrifying act is meant to teach children to grow up and face their fears (Sawin, 185). Maskers also corral and haze children, but “never whip children if they were with their parents,” indicating whipping was common practice otherwise (Gaudet, 159). Although, these actions have somewhat subsided in recent years. Violence once became so apparent among different groups that some communities had an unofficial ban on masking and restriction of whipping (Gaudet, 161). The replacement of masks by face paint includes distinctive bright colors for soldiers and “rough blackface” for the négres who also do the whipping (Sawin, 181). Mardi Gras can also be a racist festival, in which aspects such as blackface are prevalent, as seen with men cross-dressing and being able to portray themselves as “white or black” (Ware, 234). While blackface is used as “parodic commentaries on racial relationships in the region,” it is increasingly becoming controversial today, which is not a surprise (Ware, 237). An observation one could make about some of the masks and accompanied hats is that they resemble what members of the Ku-Klux-Klan would wear. However, that connection would require deeper research and discussion. It is interesting to note that maskers often chose to dress as elderly women, both men and women as comedic relief, but a relation to ageism should be investigated further (Ware, 236). This idea of savagery, or wild beasts also comes up during the festival, where individuals will mask as animals or part-human creatures by incorporating fur, feathers, beaks, and snouts (Ware, 239). This serves as a contrast to civilization, and a comedic commentary on humanity. Additionally, the wild aspect is carried out by men wearing “Indian costumes” to emphasize the savagery and primitive history of indigenous peoples, which is extremely offensive (Ware, 239). Therefore, the comedic relief the festival seems to give could just be a disguise for the racism and other discrimination abundant throughout the day.

The Universal Takeaway

Cajun Mardi Gras aids in conveying the universal message that masks provide anonymity to everyone. Masks provide an opportunity to “shed inhibitions and to take on roles for the day” (Sawin, 178). There is a role switching occurring through the use of masks, where serious individuals transform into comedic figures and shy individuals transform into leaders (Sawin, 178). Not only are masks a huge part of the culture, but individuals will also alter their physical face through the use of face painting (Sawin, 178). Gloves are also worn as to not display any identifying features. However, some disagree with the face painting, declaring it divergence from tradition since most costumes must have a hand-made mask (Ware, 228). However, any mask or any disguises are meant to be so transformative that individuals “could dance with their own wives and mothers and still remain strangers” (Sawin, 179). Individuals have the “freedom to act up, to lose himself and his inhibitions, to forget social convention, and to play the anti structural role” (Sawin, 184). Anonymity also creates an engaging game for the audience, entertainment like a guessing game of who is behind the mask (Sawin, 185). So, Cajun Mardi Gras serves as entertainment but also a public message of societal norms.

Truly, Cajun Mardi Gras is the epitome of opposing forces, with creativity being challenged and reinforced by tradition, and entertainment serving as a comedic outlet for teaching respect. Cajun Mardi Gras incorporates many different areas of juxtaposition, with chaos and flexibility emphasizing the order of the town during day-to-day activities. Additionally, Cajun Mardi Gras has increasingly given women a solid role in society by creating many of the masks and even pioneering new ways of constructing masks. The biggest role masks serve in the Cajun Mardi Gras festival is the anonymity they provide, so as family members do not recognize each other and individuals can act freely and as different than they do in normal life, and women and men are almost one being since costumes and masks make it hard for the audience to distinguish them apart. Seeing as there are questionable or insensitive practices in the festival, reassessment or revision of the festival traditions should be done. However, the festival should not be diminished in any way because it is a large part of Cajun identity that continues the history and culture of ancestors.

Bibliography

Gaudet, Marcia. “‘Mardi Gras, Chic-a-la-Pie:’ Reasserting Creole Identity Through Festive Play.” The Journal of American Folklore, vol. 114, no. 452, 2001, pp. 154-174, https://www.jstor.org/stable/542094.

Lindahl, Carl. “Bakhtin’s Carnival Laughter and the Cajun Country Mardi Gras.” Folklore, vol. 107, 1996, pp. 57-70, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1260915.

Sawin, Patricia E. “Transparent Masks: The Ideology and Practice of Disguise in Contemporary Cajun Mardi Gras.” The Journal of American Folklore, vol. 114, no. 452, 2001, pp. 175-203, https://www.jstor.org/stable/542095.

Ware, Carolyn E. “Anything to Act Crazy: Cajun Women and Mardi Gras Disguise.” The Journal of American Folklore, vol. 114, no. 452, 2001, pp. 225-247, https://www.jstor.org/stable/542097.