Masks are seen as a form of identity of an individual as they are there to conceal a person’s face and shoulders. Since the beginning of Ancient times, face and head coverings have had widespread use through all cultures including those of the Romans and Greeks. Today, the use of these coverings are still used but for slightly different purposes as we see them commonly used for martial, religious, or health purposes. Although, during Ancient times, the use of these face and head coverings had a tremendous amount of different purposes including the similar religious and marital aspects we see other uses such as purity, communication, marriage, and status. While the face and head coverings have been around for centuries, birthed during Ancient times, they have been constantly evolving in both Roman and Greek cultures. Within these cultures, there are a variety of different types of coverings that withhold different purposes that, although the purposes may differ now, carry substantial importance in our contemporary era and to an individual’s personal identity.

“Masks remain something of an enigma”

Donald Pollock

Ancient Greek Traditions

Head and face-covering practices have a lot of common misconceptions that date back to ancient times. Commonly practiced by Hellenic women, veils were also used during this time by men when in the presence of the Gods. Dating back to 750 to 30 BCE, the Himation (Fig.1) in Greek traditions, was a mantle primarily used by men and women to act as a shawl or head covering. The himation is something that can be seen on historic Greek vases ( Fig.2) where we see this rectangular cloak wrapped around or thrown over the left shoulders of Ancient Greeks. The himation typically swings over the left shoulders of the wearer where it passes under the right arm and a bulk of the fabric is met around the back. Made out of wool fabric, the himation was used for a variety of purposes. Worn over the chiton, a long tunic, until the middle of the fifth century BCE, himations made their way to be worn alone. They were typically worn and seen as an important part of their nonverbal communication; a way to express themselves without verbally using words to convey a point. The himation often showed a sign of elite status in which it was often worn by Roman and Greek aristocrats and in women it typically was used as a veil when in contact with strangers.

“As the busybody penetrates through the door of the house he ‘unveils’ its occupants to his unwanted and shaming gaze and defiles the sanctity of privacy that a house usually offers”

Llewellyn-Jones

Oftentimes, the veil during Ancient Greek times was simply just the cloak or mantle being worn and often correlated to a women’s living space. This correlation is evident as both a home and veil are seen to protect the privacy of the individual; “As the busybody penetrates through the door of the house he ‘unveils’ its occupants to his unwanted and shaming gaze and defiles the sanctity of privacy that a house usually offers”(Llewellyn-Jones 255). This analogy brings into play the ultimate desire for privacy that was trying to be achieved through these face coverings. The use of the face coverings was also primarily used to prevent what is called miasma. Miasma is the state of ritual impurity that can be described as “the lingering aura of uncleanliness” in regards to a person’s contact with the Gods. As seen in Llewellyn-Jones’ writing of Aphrodite’s Tortoise: The Veiled Woman of Ancient Greece and as a feature of Hellenism, miasma comes into play with veils as it acts as a barrier to contain the potential hazards that the female body and female sexuality are capable of. Acting as a pollutant, the use of the veil is there to ultimately help women with their lack of control over their boundaries. Men were seen as self-aware and understood their limits where a woman’s body “refused to conform or adhere to the rules of containment because it was perceived as porous and hence destructive”(Llewellyn-Jones 260). Yet, as written in Plutarch’s Saying of Spartans, it raises the question of how often a woman had to wear their veils. Writing, “When someone inquired why they took their girls into public places unveiled, but their married women veiled.” He then responds, “Because the girls have to find husbands, and the married women have to keep to those who have them!” This makes it interesting as it seems that a woman is then an object to the man where she is their property upon marriage and must be protected while a woman who is searching must expose her privacy.

CHARILLUS 197 2 “When someone inquired why they took their girls into public places unveiled, but their married women veiled, he said, “Because the girls have to find husbands, and the married women have to keep to those who have them!” -Plutarch, Saying of Spartans

Ancient Roman Traditions

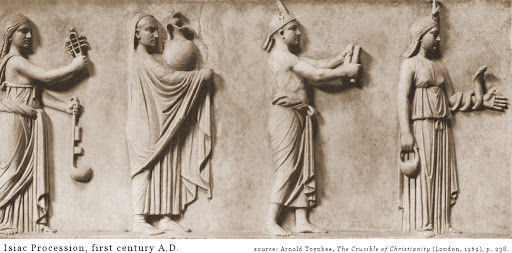

Similar to the Greeks, the Romans also had a handful of face and head covering rituals. For many, the use of covering their heads had to do mainly with religious ceremonies and maintaining the “traditional values” of the Romans. In regards to women and their face coverings, the virgin priestesses of Vesta, also known as the Vestal virgins, wore covering called a suffibulum (Fig.3). The suffibulum was a piece of square white cloth with a purple border that covered the head and sometimes shoulders that was worn prior to or during sacrifice. Similar to the suffibulum, during ceremonies such as marriage, women wore a bridal veil that was called the ricinium. The ricinium was a shaw that covered the heads and shoulders of Roman women during ancient times. However, it was until the palla came along and the ricinium seemed to have fallen out of use. Seen on Roman coins, Roman goddesses wore the palla to cover their heads to ensure modesty. This idea of pudicitia was depicted on the coins (Fig.4)with a fully clothed and veiled woman. It was regarded as a concept that regulates the sense of shame that deems a person’s behavior as acceptable.

Many Romans were expected to follow this concept of pudicitia as it was a big indicator of an individual’s morality and loyalty. Furthermore, the palla was ultimately seen as an adaptation of the Greek garment the himation (Fig.1). Worn both by men and women this piece of clothing, pallium for men (Fig.5), draped around the body and had a variety of uses. However, like the ricinium it was put to disuse by men when another piece comes along such as the toga. To women, the palla continued to be a staple garment as it suits almost all purposes and continues to be used by many cultures across the world. Pallas can be decorative with vibrant colors and patterns or a single simple color such as white or brown. In regards to men and their use of head coverings, under both Roman and Greek culture, is used to conceal feelings of shame and embarrassment. Written in Veiling among Men in Roman Corinth, “From a Roman point of view covering the head is a potential symbol of shame for a married man of non-elite status”(Massey 509).

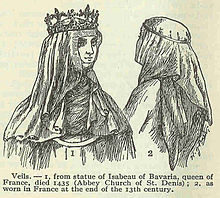

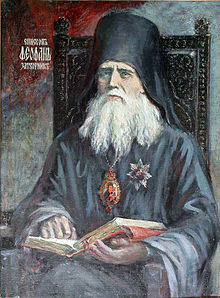

A mask, or in this case a head covering, contains a lot of identity of an individual as they are seen as a symbol of representation. “The mask works by concealing or modifying those signs of identity which conventionally display the actor, and by representing new values that, represent the transformed person or an entirely new identity”(Pollock 585). In our contemporary society, masks are continuously being used for a wide range of martial and religious purposes. They are used in a majority of the religions globally including Catholicism, Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. However, there is a difference in how they used to be treated from how they are treated now. Rather than seeing a covering as a form of social status or a symbol of a woman’s purity, they are typically seen as a sign of modesty and respect in accordance to God’s will. Furthermore, no longer is the face-covering in regards to marriage seen as important as they once were during Ancient times. Today, many brides have the opportunity to choose themselves on whether or not a veil face covering is something they choose to partake in. It no longer holds the same purposes and importance that it once did before. But again, that does not mean they are in complete extinction from society. In Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches, respectively, we see these coverings of veils (Fig. 6) being worn by nuns and religious sisters and a cylindrical hat and veil known as kamilavka and epanokamelavkion (Fig. 7) worn by the monks within monasteries. In regards to head coverings as a sense of personal identity, today, we see that they allow for individuals to have their own freedom of choice and expression. It is no longer held to a person on whether or not they want to wear one but if they feel they need one to feel at peace with themselves. In a New York Times article by Hanna Ingber, many Muslim women were interviewed in which some exclaimed no need for a veil because “God exists on the inside” while others felt it provided them confidence, peace, and a “material expression of solidarity”.

For centuries, the umbrella of head coverings has been used widely in Ancient Roman and Greek times for an array of purposes. Today, although similar purposes, these coverings have a more lenient use as there is more of a choice to the individual in whether they choose to participate in wearing them. From the beginning of times, in Ancient Roman and Greek cultures, we see the use of these coverings for nonverbal communication, a sense of purity of a woman from her husband, a man’s social status, and as a form of privacy and protection of a woman’s body. In contemporary times, we see these specific purposes declining but more of a sense of modesty and dedication to one’s faith. In the end, the use of these facial coverings has provided individuals with a sense of personal identity and will continue to be used upon a person’s personal preference.

Bibliography

Ingber, Hanna. “Muslim Women on the Veil.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 27 May 2015, www.nytimes.com/2015/05/28/world/muslim-women-on-the-veil.html.

Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd. “House and Veil in Ancient Greece.” British School at Athens Studies, vol. 15, 2007, pp. 251–258. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40960594. Accessed 27 Apr. 2021.

Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd. Aphrodite’s Tortoise: the Veiled Woman of Ancient Greece. The Classical Press of Wales, 2010.

Marlowe, Michael. “Headcovering Customs of the Ancient World An Illustrated Survey.” Headcovering Customs of the Ancient World, www.bible-researcher.com/headcoverings3.html.

Massey, Preston T. Veiling among Men in Roman Corinth. Indiana Wesleyan University, 2018.

Plutarch. “Sayings of Spartans.” Plutarch • Sayings of Spartans – 208B‑236E, penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/plutarch/moralia/sayings_of_spartans/main.html.Pollock, Donald. “Masks and the Semiotics of Identity.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 1, no. 3, 1995, pp. 581–597. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3034576. Accessed 29 Apr. 2021.