The Theatrical Origins and Language of Venetian Carnival Masks

The practice of masking during carnival celebrations dates back all the way to the fourth century BCE and was widespread throughout Europe by the fifteenth century. These colorful disguises were most popular in Southern Europe, where festivals were more common and masks were more elaborate, becoming particularly famous in Venice, Italy (Carpenter, 9). The practice of masking helped to create atmospheres of freedom and opportunity, allowing masked participants to remain anonymous and therefore drop their inhibitions and shames to let themselves have fun. Over the long history of Carnival in Venice, the decorative face masks of revelers have been both a staple of the celebration and the source of much criticism. While there were a lot of examples of objections against masking and celebrating Carnival from both religious and social standpoints, that never stopped both men and women from participating.

Masking was traditionally a man’s game. For each Carnival celebration, men would dress up and roam the streets while women played the important role of participating as spectators to their elaborate masquerade. However, by the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries masking had become a unisex practice (Carpenter 10).

One of the most prominent criticisms of Carnival and masking was the opportunities for mischief that it created. Venetian Carnival masks had many designs and inspirations, with characteristics that could either construct or erase the essential aspects of a reveler’s identity. Unlike celebrations like Saturnalia, the debauchery that accompanied carnival was not rooted in any subversion of power but from the illusion of freedom and suspension of truth that the masks provided partygoers (Quinn, 74). This illusion of freedom, this distance from personal accountability, could be created using two distinct kinds of masks: those that created an elaborate false identity and those that erased individuality to make you just one of the crowd.

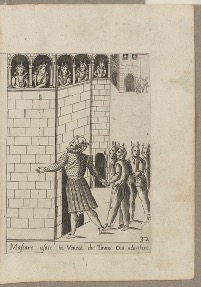

Traditional Carnival masks that construct false identities in order to conceal the reveler beneath often drew their inspiration from the commedia dell’arte, which was an early form of professional Italian theatre that utilized character archetypes in distinctive masks and costumes. These archetypes were static and predictable for long enough that they became staples of Italian storytelling and visual art, and many iconic carnival masks are in the style of these characters, including the Zanni, Pantalone, and Colombina masks. While these masks were used to create characterization in theatre, they were then subverted to erase identity when worn by carnival-goers in the crowd. Commedia dell’arte-inspired masks are most frequently half-mask designs since actors who wore similar masks on stage needed the lower portion of their face free to deliver their lines effectively.

The Zanni mask is one of the most distinctive of Venetian carnival masks, despite being a secondary character archetype in most traditional theatre. Zanni is the name of an overarching group of stock characters that the commedia dell’arte utilized, ascribed to clowns and stupid servants such as Harlequin. The Zanni mask is a half-mask characterized by a scrunched, low brow and a long thin nose, both of which were considered signifiers of stupidity. The lower the brow or longer the nose, the less intelligent the character being portrayed. While bumbling and crude, Zanni characters were also known for their nimbleness and were the most animated among their cast. Their lack of intelligence was sometimes a source of conflict, sometimes a source of comedic relief, but the distinctive shape of the mask helps it stand out in a crowd and makes it a favorite among modern carnival attendees.

Pantalone is another stock character that was commonly portrayed with a half-mask and exaggerated features. This mask style is most often marked by a high brow and a prominent hooked nose, paired with pronounced wrinkles and bushy eyebrows to channel the appearance of a wizened old man. In contrast to Zanni masks, these deep-set wrinkles paired with the high forehead were used to signify wisdom, and sometimes despair. The Pantalone mask is traditionally worn by men and continues to be worn to celebrations, but the sad old man archetype has seen a decline in popularity in modern carnival.

The Colombina mask is based on the character of Colombina in the commedia dell’arte, a well-known and well-loved young female character who was often a maid or spouse in plays. Despite deriving directly from the commedia dell’arte, the Colombina mask is a relatively modern invention. Colombina in traditional theatre was an unmasked character archetype and the actress would instead be signified by her heavy makeup and ornamentation. On occasion, the character would wear a domino mask, which has been adapted into today’s popular party mask. While the traditional form of the Colombina character wore no mask, a common story for the origin of this domino mask is that the character of Colombina was so vain that never wanted to obscure her features with a full mask. The Colombina mask is a heavily decorated half-mask, covering only the upper portion of the face and held in place by being tied by a ribbon or held in position with a baton. In modern carnival, both men and women wear the Colombina mask.

While these types of character masks were and are very popular, they are only one side of the coin. Where commedia dell’arte masks were constructive, establishing an expectation based on the source, other masks were subtractive and designed to completely erase individuality and identifying factors.

The bauta mask is one mask design utilized by Carnival-goers who wished to stay anonymous. These masks were a blank slate, with simple decorations or no decoration at all, a wide nose, and square jaw that extended outward instead of curling back around the face. With these exaggerated features, just about any face could fit beneath it and be perfectly concealed without discomfort. The outward flare of the bottom of the mask was specifically so that the wearer could eat, drink, and talk without needing to remove it and reveal their identity. In a crowd of masks, “the carnival bauta was nearly uniform, and as such it erased the particular identity of the wearer; it effaced not only physiognomy but often class, gender, or even race” (Quinn 74). This made it one of the best choices for both men and women who wanted to celebrate Carnival without the burden of identity. This anonymity might erase the power held by those of the ruling class or high officials, but it also erased the inherent vulnerability of their power as well as created power for those who had none.

A mask that was more traditional for women was the moretta, which was a small oval mask, dark in color and only wide enough to cover the center of the face. Instead of straps, the moretta was held in place with a button or bit that the wearer would keep between their teeth. Because this design rendered the wearer mute, another name for it was the muta or servetta muta.

The moretta mask fell out of fashion in the late 18th century, but before that it was an integral piece in a woman’s game of seduction during the festival. By covering just a small area in black velvet, a woman’s pale skin was thrown into sharp contrast and also turned her face into a treasure to be earned. This mask design has been immortalized in artwork such as Rosalba Carriera’s Portrait of a Woman with Mask (left) or Clara the Rhinoceros by Pietro Longhi (below). Pietro Longhi painted a number of Carnival scenes, including Clara the Rhinoceros who was exhibited in 1751 as a Carnival spectacle.

Traditional bauta masks are handcrafted from paper-mache and then decorated with filigree or paint as the artist sees fit. The moretta is covered in black velvet, for the aesthetic advantages of both the dark color and the soft, expensive material.

Masks such as the bauta and the moretta were also favored by gamblers, because of their ability to render the wearer indistinguishable. In high-stakes environments, such as Venice’s most renowned gambling hall, the Ridotto, masks were part of a mandatory dress code for visitors. While this sometimes created a barrier for those who could not afford the correct costume, the casino was still open to anyone with enough money for a mask and a buy-in. This meant that anyone, of any social class or status, could end up standing next to each other to win and lose money all evening. Masks were required both by law and by the rule of the casino so that “if great gains or losses risked a sudden reversal in the social order, the mask could lessen its effects by concealing exactly who was winning and losing” (Johnson 408). Not only did they level the playing field by removing any threat of intimidation or retribution, but they also reduced class tensions and wounded pride.

Una McGowan ARTH300: Fashion, Art, & Politics Dr. Alla Myzelev Spring 2021

Bibliography

Carpenter, Sarah. “Women and Carnival Masking.” Records of Early English Drama 21, no.2 (1996): 9-16. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43505418.

Johnson, James H. “Deceit and Sincerity in Early Modern Venice.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 38, no. 3 (2005): 399-415. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30053403.

“Making the Masks: Handcrafting Venetian Masquerade Masks.” Italy Mask: Authentic Venetian Masks. https://www.italymask.co.nz/Behind-The-Masks/Making+the+Masks.html.

Quinn, Michael L. “The Comedy of Reference: The Semiotics of Commedia Figures in Eighteenth-Century Venice.” Theatre Journal 43, no. 1 (1991): 70-92. www.jstor.org/stable/3207951.

“The Bauta: The Queen of Venetian Masks.” Ca’ Macana, www.camacana.com/en-UK/bauta-venetian-masks-history.php.

“The Moretta mask: Venetian mask of seduction.” Ca’ Macana. https://www.camacana.com/en-UK/moretta-venetian-mask.php.