“Lives are at risk because we do not have enough supplies.” This statement by Carlos Montiel, president of the Venezuelan Red Cross, echoes the challenges faced by millions of Latin Americans in the face of the Coronavirus pandemic.

Covid-19 is creating an environment in Latin America that is receptive to authoritarian transition, including economic crisis and electoral disarray.

Bolivia – Covid-19 and Electoral Turmoil

The electoral process of Bolivia was impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic perhaps greater than that of any other country. Before the pandemic it was already suffering through a major crisis of leadership, as the current government had not been elected but was put into power after the previous November’s election results had been overturned. The reasoning for this was based on claims of election rigging on the part of then-President Evo Morales and his party, the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS), with these claims being controversial and not supported by conclusive data. The rerun election that was planned for May, in which the party that had been ousted would have had a chance to regain power, was delayed due to the effects of the pandemic making in-person voting dangerous. While it was originally planned to be held in September, the election was once again delayed. This past October, the election was finally held, and the MAS party regained power. What this essentially means is that for almost a full year, a party that was not democratically elected and that did not have the support of the populace was in power, with this period of time including the beginning and, as of today, the majority of the pandemic.

Though many governments across the world have struggled with handling Covid-19, Bolivia stands apart as being a democratic country without a dictator or otherwise unelected leader that still had to go into the worldwide pandemic with a government not chosen by the people. They suffered not because of mishandling by a government they chose, but because a government that basically put itself into power without electoral results supporting them was then unable to successfully deal with the pandemic. Whether the original government would have done better is of course impossible to know, and whether the new government will do better is yet to be seen, but the situation in Bolivia does show the intertwined nature of Covid-19 and politics, as the government would not have been in power for as long as they were if it had not been for Covid-19, while at the same time Covid-19’s spread in Bolivia may not have been as bad as it was if they had not been in power for so long.

Colombia- Democratic Backslide from Covid-19

Economic turmoil, declining system political culture, and minority disenfranchisement due to the Covid-19 pandemic in Colombia are contributing to a significant democratic backslide, facilitating opportunities for an authoritarian shift in the coming years.

Colombia is on the verge of an economic crisis due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In November, Colombia raised its 2020 target deficit from 8.2% GDP to 8.9% of GDP, and expects the country’s economy to shrink by 6.8% as a result. The country already has a political culture with little trust in government institutions. In a study of Colombian political attitudes between 2017-2020, 60% responded with “not very much confidence” in their national government.

A shrinking economy will only exacerbate existing distrust of the Colombian government and contribute to a further degradation of public institutions. Colombia is currently a hybrid regime, in large part because of the rampant corruption that exists at all levels of national and subnational governments; In 2019, Colombia ranked 37/100 in the corruption perceptions index (CPI), the lower number indicating higher levels of perceived corruption. Declining public trust and a weakened economy due to Covid-19 are sure to result in increased corruption, pushing Colombia further in the hybrid regime spectrum towards authoritarianism with less accountability in political parties and elections.

Additionally, Covid-19 has not affected everyone equally in Colombia. Indigeonous populations, many in isolated rural areas without adequate access to healthcare and testing, have been disproportionately hurt by the virus. This is likely to further disenfranchise minority groups in the Colombian political process, allowing legislatures more leeway in ignoring minority concerns and focusing on more privileged constituents. A key aspect of authoritarian regimes is the inability of minorities to effectively influence government, which is conversely a critical component of liberal democracy. If the pandemic maintains its current course of lopsided destruction for the rural, indigeouns poor, the Colombian government will more closely resemble authoritarianism in its absence of minority representation and the lack of support for minority crises.

Venezuela – Stronger Authoritarian Rule during Covid-19

Along with Bolivia and Colombia, Venezuela too has seen an intrusive government. While already having been perpetrators of a grand scheme to centralize significant amounts of power to President Maduro and his cohort of loyalists, there has been increased authoritarian rule during the recent pandemic. For instance, public dissent against the government regarding their Covid-19 response is currently grounds for arrest. This is not an unusual response by the government, where they consistently crack down on political opponents (although recently President Maduro pardoned hundreds before the upcoming election in an effort to give himself greater legitimacy) and is emblematic of Maduro’s tactics to maintain his foothold on the presidency.

Venezuela has a history of authoritarianism, although it has been exposed more recently due to Maduro’s significantly lower popularity compared to his predecessor Chavez. Chavez’s popularity, which was typically above 50 percent during his tenure, contrasts that of Maduro’s, who has seen struggling popularity numbers (well below 50 percent) even only a few years after Chavez’s death. Nevertheless, Maduro’s handling of Covid-19 has been abysmal and his indifference toward the economy, where he has done nothing to compensate for the stoppage in oil drilling, has made an already struggling nation become desperate. Charities which would normally have a larger stockpile of food have been reduced to much less amid looting and an economic depression that has caused closures of businesses who normally would have donated to these charities. Moreover, because Maduro has not declared a humanitarian emergency, primarily to prevent the narrative that his government has failed, he has “[made] it impossible for international agencies, like the Red Cross, UNICEF and the World Food Programme, to airlift and distribute the tons of supplies that Venezuela needs.” The pandemic has also caused food prices to skyrocket, increasing 80 percent, and has led to 70 percent of hospital workers emigrating. Again, this reveals the incompetence exhibited by an authoritarian whose actions stem from his attempt to maintain power.

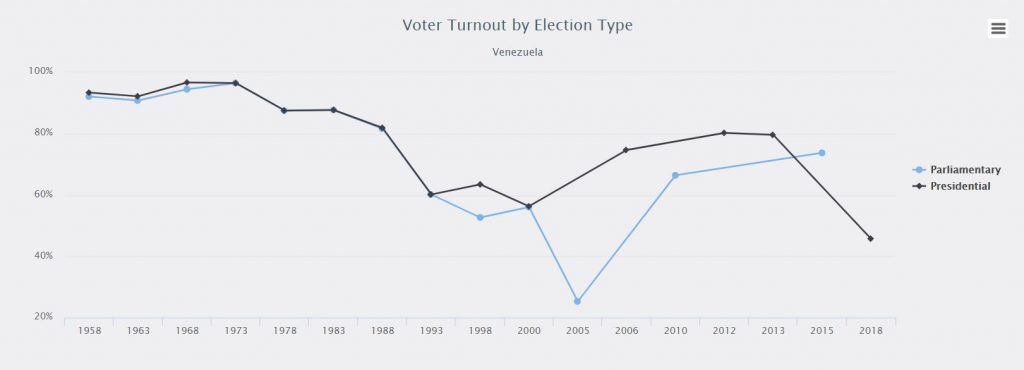

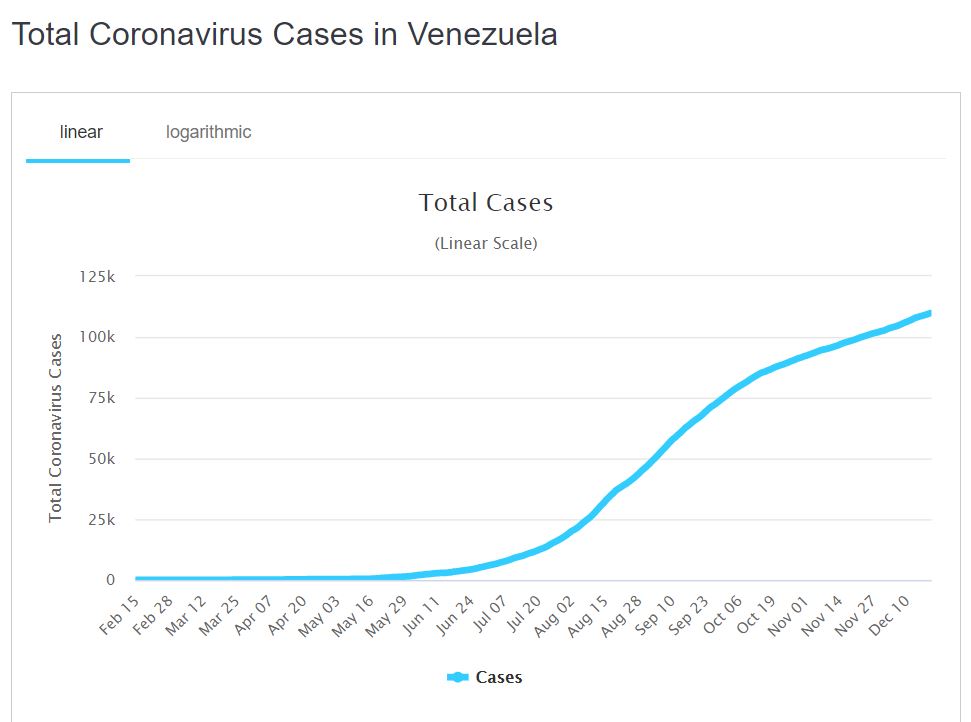

Recently, turnout for the Venezuelan National Assembly saw only a 31 percent turnout which was “less than half the 70 percent who voted in the legislative election in 2015.” Granted, this was due to a boycotted election by Maduro opponents, it still exemplifies the corruption that plagues the government. Moreover, consider the Covid-19 data in the country. With full control over the data, Maduro has the ability to downplay the impact it has had on the population. By centralizing the testing, Maduro has created a situation in which nobody else has the authority to diagnose coronavirus and has inhibited the transparency of cases even to top Venezuelan public health officials. Venezuela, thus, has seen an ineffective government continuously put its citizens in danger to uphold its facade of being a strong regime.

Covid-19 and Rising Authoritarianism in Bolivia, Colombia, and Venezuela

The Covid-19 pandemic has produced a plethora of opportunities for the rise in authoritarianism and backslide of democracy in these three countries. The ability for Bolivia’s undemocratically elected government to remain in power was a result of the pandemic’s capacity to disrupt the election process and encapsulates the ability for authoritarianism to thrive in a time of disarray. In Colombia, economic turmoil, declining trust in government, and dispporpoitate effects on minority populations from the coronavirus pandemic have all created an environment that is ripe for an authoritarian shift. Finally, the manipulation of its case numbers and inaction in a time of economic disaster (preventing much needed aid across the country), reveals Venezuela’s true intentions to maintain its image as a strong and effective government. Each of these countries provide valuable insight into how the Covid-19 pandemic allows for authoritarianism to flourish and the backslide of democracy to occur and be exploited in order for the government to gain a significant amount of power over its country, a startling revelation due to these countries already having exhibited such behavior prior to the pandemic.

Sebastian Stone is a freshman at SUNY Geneseo who is currently undecided, and planning on graduating in 2024.

Samson McKinley is a sophomore at SUNY Geneseo majoring in International Relations and graduating in 2023.

Colin Beasor is a senior at SUNY Geneseo majoring in Political Science and minoring in Business Studies, graduating in 2021.

References:

Anatoly Kurmanaev and María Silvia Trigo, “In Bolivia, A Bitter Election Is Being Revisited – The New York Times.” Accessed December 21, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/07/world/americas/bolivia-election-evo-morales.html.

Anthony Faiola and Rachelle Krygier, “Evo Morales Resigns as Bolivia’s President after OAS Election Audit, Protests – The Washington Post.” Accessed December 21, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/bolivia-to-hold-new-elections-after-protests-and-international-criticism/2019/11/10/4778e842-03b2-11ea-ac12-3325d49eacaa_story.html.

BBC News, “‘I Have to Queue for 13 Hours to Get Fuel.’” BBC News. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-latin-america-52640757.

Corruption Perceptions Index, “Colombia.” Transparency International, 2018. Accessed December 21st, 2020. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2019/results/col

Herrero, Ana Vanessa. “Maduro Consolidates Power in Venezuela, Dominating Election Boycotted by Opposition.” Washington Post. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/venezuela-election-national-assembly-maduro-guaido/2020/12/06/8a9fee74-35d2-11eb-8d38-6aea1adb3839_story.html.

Herrero, Ana Vanessa, and Anthony Faiola. “Venezuela’s Maduro Pardons More than 100 Political Opponents Ahead of Elections.” Washington Post. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/venezuelas-maduro-pardons-more-than-100-political-opponents-ahead-of-elections/2020/08/31/c5770df0-ebbf-11ea-b4bc-3a2098fc73d4_story.html.

Herrero, Ana Vanessa, Anthony Faiola, and Mariana Zuñiga. “As Coronavirus Explodes in Venezuela, Maduro’s Government Blames ‘Biological Weapon’: The Country’s Returning Refugees.” Washington Post. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/coronavirus-venezuela-migrant-maduro/2020/07/19/582c659c-c518-11ea-a99f-3bbdffb1af38_story.html.

Inc, Gallup. “Special Briefing: Chavez’s Legacy and Venezuela’s Future.” Gallup.com, April 12, 2013. https://news.gallup.com/poll/161756/special-briefing-chavez-legacy-venezuela-future.aspx.

Inc, Gallup “Venezuelans’ Approval of Leadership Remains at Record Low.” Gallup.com, May 20, 2016. https://news.gallup.com/poll/191663/venezuelans-approval-leadership-remains-record-low.aspx.

Julie Turkewitz, “How Bolivia Overcame a Crisis and Held a Clean Election – The New York Times.” Accessed December 21, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/23/world/americas/boliva-election-result.html.

Newton, Creede. “Colombia raises target deficit due to pandemic: COVID-19 news.” Aljazeera, November 13th, 2020. Accessed December 21st, 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/11/13/us-schools-suspend-classes-as-covid-cases-grow-live-news

NPR.org. “Coronavirus Comes To Venezuela : The Indicator from Planet Money.” Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/08/11/901501100/coronavirus-comes-to-venezuela.

NPR.org. “‘Lives Are At Risk’: Venezuelan Charities Struggle Under Shortages And Intimidation.” Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2019/06/11/731648645/lives-are-at-risk-venezuelan-charities-struggle-under-shortages-and-intimidation.

Our World in Data, “Colombia: Coronavirus Pandemic Country Profile.” Our World in Data, 2020. Accessed December 21st, 2020. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/colombia?country=~COL

PBS NewsHour. “Venezuela’s Humanitarian Crisis Has Only Worsened under COVID-19,” September 17, 2020. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/venezuelas-humanitarian-crisis-has-only-worsened-under-covid-19.

Polanco, Anggy. “Despite COVID-19, New Wave of Venezuelan Migrants Heads to Colombia.” Reuters, October 15, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-venezuela-migrants-idUSKBN2702IW

Sequera, Angus Berwick, Vivian. “In Run-down Caracas Institute, Venezuela’s Coronavirus Testing Falters.” Reuters, April 17, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-venezuela-tests-in-idUSKBN21Z1BR.

Trigo, María Silvia, Anatoly Kurmanaev, and Allison McCann. “As Politicians Clashed, Bolivia’s Pandemic Death Rate Soared.” The New York Times, August 22, 2020, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/22/world/americas/virus-bolivia.html.

Universal Health Coverage Partnership, “Colombia responds to COVID-19 with an intercultural health model.” United Health Coverage Partnership, November 5th, 2020. Accessed December 21st, 2020. https://www.uhcpartnership.net/story-colombia/

World Values Survey, “Colombia.” World Values Survey, 2017-2020. Accessed December 21st, 2020. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSOnline.jsp