“If the people cannot trust their government to do the job for which it exists – to protect them and to promote their common welfare – all else is lost.” Barack Obama’s statement is more applicable to today’s world than ever before.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has tested and shifted the trust of governments all around the world as it is a public health and economic crisis that has never been experienced before. Political trust refers to the “belief that rulers are generally well-intentioned and effective in serving the interests of the governed” (Hague et al. 2019). During the COVID-19 pandemic, governments are assessed on their effectiveness based on the success of their preventative policies, which is based on the government’s balance between public opinion and science. Political trust is a very powerful and malleable aspect of politics; as much as it can be shaped by the actions of leaders, it can affect the actions of the citizens. In Western Europe, the cases of Greece, Sweden, and the United Kingdom have taken vastly different approaches to get back to normal. Despite the different approaches, a clear trend emerges: a government that primarily bases its pandemic strategy on science is able to get its citizens to cooperate and trust its decisions. Without the trust of the people, the governments have seen the pandemic get worse before it gets better, indicating that trust plays an important role in indicating COVID-19 strategies globally.

How previous tensions between citizens and the government affect trust in policies

The precautionary measures against COVID-19 that are being implemented around the globe depend heavily on trust between citizens and government. With no trust in their policymakers, citizens are less likely to follow measures that are intended to protect them. Within this phenomenon, an interesting trend emerges; nations that were, before the pandemic, generally trusting in their government and in their fellow citizens tend to have higher rates of success with lockdowns and other such measures. Nations with pre-existing tensions between the government and its citizens, however, are struggling to encourage citizens to follow the measures that have been laid out. Previous conflicts between the government and the governed, then, comes to play an important role in the effectiveness of a country’s COVID-19 strategy.

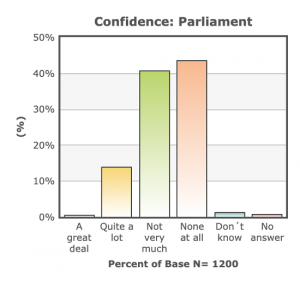

Greece – It is no secret that Greece has struggled with politics and economics in the past. Previous tensions have run high after facing a severe financial crisis and recently experiencing a flip in parliamentary majority power. In 2017, before Greece’s most recent elections, and as seen in Figure 1, 43.3% of citizens had no confidence at all in parliament, and 40.7% reported having very little confidence (World Values Survey 2020).

While trust levels and confidence in parliament have not been officially assessed since the most recent election where the conservative New Democracy won 39.9% of the vote over the previous majority party, Syriza, there is cautious optimism among experts (POLITICO 2019). After seeing an ineffective and wildly unpopular parliament under the Syriza party, there was political and social unrest in the already economically unstable country (Halikiopoulou 2019). Still, the turnaround to a new party has increased the chances for trust in new policies. Thanks to the legislative shift, Greece has seen some positive strides in light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

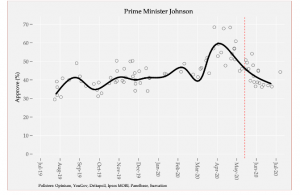

The United Kingdom – The gravity of the COVID-19 pandemic was not fully realized in the United Kingdom until March of this year. March 2020 provides a significant turning point for the United Kingdom’s Parliament and Prime Minister Boris Johnson. Before March, Johnson’s monthly approval rating typically rested around forty percent. His approval rating dipped between February and March as seen in Figure 2 (Jennings et al. 2020).

Johnson was named Prime Minister in 2019 after his predecessor Theresa May resigned and maintained his position following the 2019 General Election. Johnson was plagued by controversy while campaigning and following the election. For instance, prior to his role as Prime Minister, he was a journalist known for valuing “a headline-catching story about the EU over factual accuracy” and as foreign secretary, he constantly made “diplomatic gaffes” (Rose 2020). He was also elected following the referendum that decided that the United Kingdom would leave the European Union which led to divisions within his Conservative Party and overall difficulty in managing Parliament. At the beginning of his term, Johnson only appointed Cabinet Ministers that aligned with the idea of a hard Brexit and fired those voicing concerns. He even discontinued the meeting of Parliament for six weeks to prevent interference in his negotiations with the European Union. As a result, courts in the UK repealed his actions in the UK Supreme Court which declared Johnson’s actions unlawful (Rose 2020).

Additionally, tensions between England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland have been developing due to the unitary structure of the United Kingdom’s government. Since England is the home of the government, the people there receive the most attention at the expense of the other three regions. As a result, people from Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland are less trusting of Johnson and his administration (McGee 2020).

Following that dip and during the early days and uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic, his approval drastically increased to sixty percent. Between April 2020 and mid-May, Johnson’s approval rating steadily decreased but remained higher than typical. When examining the graph below at face value, the sudden increase in the support for the Prime Minister may seem surprising considering Johnson’s prior controversy, inability to cooperate with those holding different views, and forceful attempt to achieve Brexit especially when you simultaneously consider the loss of life and jobs. However, Prime Minister Johnson, along with other Members of Parliament were evaluating and trying to cope with a health, economic, and social emergency of epic proportions that permeated domestic and international politics alike.

Unlike anything ever experienced before, the people of the United Kingdom stood behind their government as they navigated this uncertain storm to what citizens hoped was to the best of their ability. When evaluating the data in this context, it is not surprising; this occurrence fits into the phenomenon known as the rally-around-the-flag effect. Simply put, the rally-around-the-flag effect is a short-term spike in support or positive favor for the national leader during an international emergency. In the midst of a pandemic and the major detriments invading all sectors of life and politics, the people of the United Kingdom had supported their government.

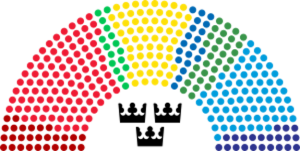

Sweden – For decades, Sweden has had one of the most trustful dynamics between citizens and government in the world. Swedish citizens trust that the government is always working in their best interest, resulting in a “very high level of confidence among Swedish citizens towards authorities and the government” (Edwards, 2020). This level of trust would have served Sweden well coming into the pandemic, if only they were able to maintain it. Unfortunately, pre-existing tensions from the 2018 election (which was, by all accounts, unorthodox) ultimately thwarted the trust that had been so steadily built between the government and citizens for decades. Sweden’s political culture and the multiparty system often force several parties to form a coalition if they intend to retain a majority in parliament. In 2018, as seen in Figure 3, this scenario came to fruition; no single party won the majority, leaving Sweden with a hung parliament until a suitable coalition could be formed.

Both the Social Democratic Party (shown in pink to the left) and the Moderate Party (shown in light blue to the left) were able to secure a large percentage of the final vote, with the Social Democrats gaining merely one seat more than the Moderates (Anderson, 2019). Neither party could, however, gain enough support to form a majority due to the highly fragmented vote and pre-existing party tensions within the Swedish legislature, also known as the Riksdag. The formateur announced after two weeks of high anticipation that he was unable to form a suitable coalition. The issue persisted, passing through the hands of two more formateurs before a solution could finally be reached (Edwards, 2020). Nearly four months after the election, a compromise was made and an unsteady alliance between the Social Democrats, Centres, Greens, and the Liberal formed a majority in the government (The Local, 2020a). As Torbjorn Larsson, a political scientist at Stockholm University, marveled “The political situation in Sweden has not been so complicated in almost a century,” (Anderson, 2019). Several party leaders also weighed in on the unconventional formation, with Busch Thor, the leader of the Christian Democrats, notably calling it “an unholy alliance” (Anderson, 2019). The unusual configuration of government and the highly dispersed votes both suggested that Sweden is transitioning into a form of politics “more like those across Europe, with greater fragmentation,” (Anderson, 2019). This fragmentation drew cracks not only among the population but within the government itself. Nearly half of citizens reported that they did not believe the unstable government would last its full term in February 2019, only a month after it was formed (Anderson, 2019). This uncertainty obviously led to a dent in the trust that the country had touted for so long, as citizens couldn’t even trust in the government’s stability, much less its ability to lead righteously. Thus the political situation in Sweden upon entering into the pandemic was fragmented and highly uncertain.

How trust impacts the effectiveness of government policies

As for how trust plays into the pandemic, each country varied in the effectiveness of its policies based on levels of trust in government strategies and policy. As evaluated in each case study, various other factors can come into play when it comes to the effectiveness of government policy, but trust is key to see success.

Greece – With a new degree of trust in the legislature, Greece has managed to implement various effective policies in regards to COVID-19. Back in February of 2020, Greece began to consult with a new National Experts Committee on Public Health and updated the head of their Ministry of Health to a professor specializing in pathology and infectious disease (Ladi 2020). Thanks to their fast-acting and ability to shut down schools and restrict large gatherings, Greece was able to contain the virus before a single virus-related death was recorded (Ladi 2020). Proactivity with the newly elected parliament, however, is not the key to success in Greece, rather the public’s long-standing compliance with these policies. By implementing evidence-based policies, the government has managed to not only gain the political trust of their people but maintain it (Ladi 2020). After the 2019 election, Greek citizens experienced a newly invigorated trust in parliament, encouraging them to comply with the policies being implemented in the country.

Reinvigorated trust is not the only factor in Greece’s success in combating COVID-19. Due to initial compliance from the population, a positive reinforcement cycle emerged, looping compliance with low cases and a low mortality rate, making Greece one of the few “success stories” in response to COVID-19 (Moris et al. 2020). Despite being the most medically understaffed country in the European Union, with a 1:16 ratio of specialists per person, Greece has maintained some of the lowest mortality rates even after re-opening thanks to this compliance and newfound trust in parliament (Fouda et al. 2020).

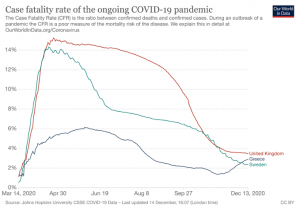

As seen in Figure 4, in a widespread comparison between Greece, the United Kingdom, and Sweden, despite long-standing financial struggles and a weak medical system, has managed to keep their curve lower than the two less-burdened countries thanks to their level of political trust and compliance (Ritchie et al 2020). Up until the final phase of their re-opening, Greece has managed to subdue the COVID-19 mortality rate, not because of their medical expertise or astronomical budget, but because of the compliance from their population which stems from the trust that the legislature is making the right choices and operating in the most effective manner possible. Henceforth demonstrating how political trust has been a crucial factor in Greece remaining a success story rather than a failure tale.

The United Kingdom – As mentioned before, Prime Minister Johnson’s approval has declined as the COVID-19 pandemic has continued. Unsurprisingly, this is the result of the United Kingdom being one of the most affected European countries. At the end of October, the United Kingdom reached an astounding one million COVID cases and fifty thousand COVID-related deaths. As a result, the government enacted a national month-long lockdown in November. At the beginning of the lockdown, citizens were hesitant to follow as they didn’t want to be stuck inside anymore, as seen in Figure 5.

In fact, shops and public transportation were crowded. One stationary shop even claimed their services were essential to stay open. The owner of a busy chocolate shop was told to shut down since the business wasn’t essential. Still, the owners plan to open again, explaining, “If the government had set out rules that people could follow from the beginning, then we wouldn’t be in the situation we’re in now” (Mueller 2020). The shop owner is referring to the United Kingdom’s initial strategy of herd immunity. This strategy focused primarily on shielding vulnerable populations rather than preventing the spread of COVID-19. Johnson was recorded saying that the solution was “for the majority of the population to become infected” and “a nice big epidemic”(Horton 2020). Despite the initial defiance, once people began to take the precautions seriously, the second national lockdown resulted in an astounding thirty percent decrease in England’s COVID-19 cases; even more effective results were seen in the more heavily impacted north as cases decreased by fifty percent. Following the lockdown, the transmission rate (abbreviated to the variable R) has also decreased following the November lockdown. Across the many cities, the average R-value fell from 1 to 0.88 (Braithwaite, Reynolds 2020).

While cases continued to increase among the public, the most well-known figures in the United Kingdom’s government and response force were also diagnosed with COVID-19. The most notable include Health Secretary Matt Hancock, Prince Charles, Chief Medical Advisor Chris Whitty, and Boris Johnson himself (Landler, Castle 2020).

A number of leading political officials across the United Kingdom have been caught breaking the restrictions and preventative measures they as the governing body put in place. The most prominent and notable instances include Margaret Ferrier, a Scottish Member of Parliament who traveled to London and then back to Scotland while having symptoms of COVID-19; she later tested positive. Johnson’s senior aide, Dominic Cummings, was caught traveling to London, a city under strict lockdown, to visit his parents while he was infected with COVID-19. From South Wales, another Member of Parliament posted a picture after traveling to celebrate his elderly father’s birthday, albeit the pair were socially distant (Independent 2020).

The fact that the government’s leading officials have been able to contract the virus despite the measures and policies put in place have called their judgment and said policies into question. How are they to expect their constituents to follow rules they hypocritically break? How can the United Kingdom citizens trust the government when the rules put in place are still not enough to keep them safe? Political trust and confidence have an enormous impact on whether or not legislation enacted to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 is successful. The relationship between trust/confidence and the effectiveness of preventive measures is not a one-way street. Citizens are unlikely to follow scientific and governmental authorities’ advice and guidance if they lack confidence and trust in their decisions. Conversely, if the government has proven itself capable of creating an effective strategy, its constituents are likely to follow it.

The tensions between the four regions of the United Kingdom have also trickled down into the pandemic response. When Boris Johnson addressed the nation during the spring, Nicola Sturgeon, the Scottish First Minister, took the screen first. Sturgeon said she had “not yet seen the full detail of the plan, so it’s not possible for us to simply adopt it for Scotland” and would still promote staying home despite Johnson shifting gears and asking the people to “stay alert” (McGee 2020). Sturgeon’s message illustrates the lack of trust that the regions outside of England feel towards the government and how little power the government over them. Over the years, the Parliament had devolved powers to regional bodies, so the Parliament’s division and lack of support are not surprising. In fact, Northern Ireland and Wales enforced more restrictive measures than the ones instituted by Johnson. Northern Ireland closed schools and pubs, and Wales discontinued travel from hotspots within the United Kingdom (Kirka 2020).

Sweden – Trust has a huge impact on any policy released by the government; if there is no connection between the policymakers and their constituents, citizens may not feel inclined to follow the outlined rules at all. This is especially true of policies relating to the COVID-19 pandemic, in particular those released by Sweden. Sweden has taken an unusual approach to control the spread of coronavirus, in that it has released almost no mandates or restrictions on activity. Sweden has officially limited gatherings in groups of over 50 but refuses to take further measures. The lead epidemiologist in Sweden has openly called closing the borders “ridiculous” and advises against wearing face coverings at all. Rather than official policies, Sweden issues recommendations, which they trust that citizens will follow pertinently enough to keep the country safe. Individuals are “instructed to use their judgment and to take individual responsibility within a framework that rested on mutual trust, rather than top-down control” (Trägårdh, 2020). The government has recommended that individuals limit their movement as much as possible but has not released any official policies backing this recommendation.

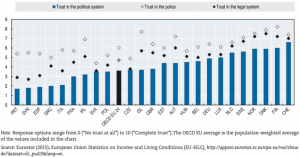

This approach is certainly an outlier globally; many anti-lockdown advocates point to Sweden as an archetype: a model that can be followed to protect communities while still preserving their individual freedoms. However, Swedish officials warn against other countries following in their footsteps. They warn that the government and its people’s mutual trust is necessary for this strategy to be effective. Sweden has historically had high levels of trust; it is, according to the 2015 Eurostat study shown above, one of the most highly trustful countries in the OECD and, indeed, in the world (Ortiz-Ospina 2016). However, these levels were measured in 2015, before electoral tensions caused a sudden drop in this mutual trust. The beginning of the pandemic saw general trust in the authorities’ rulings, but these rulings were flawed. The decisions not to lockdown and discourage masks in Sweden caused a significant worsening of the conditions. As of October 12th, Sweden had a 58.4 per 100,000 death rate, the 12th highest in the world. The country’s situation is not losing momentum either, with daily average cases increasing 173% in September (Bjorklund 2020). This, combined with pre-existing tensions, caused a steep drop in approval of the government. In May 2020, 50% of the population thought that the government was handling the crisis well. This number has since steadily declined to 34% as of September (The Local, 2020b). The citizens express their frustration not only with the parties in control of the government but also those in opposition; the opposition saw a 16% drop in levels of trust, leaving them with only a 14% approval rating (The Local, 2020b). This declining trust in Swedish authorities means that less of the population will follow the coronavirus guidelines, that the situation will worsen, and that trust will decline even further.

Public opinion and science; how much each affects policymakers’ decisions

Ultimately, a key component in maintaining political trust is the value of public opinion and how policymaker decisions reflect it. Without public approval, policies can be met with apprehension, but in the case of a pandemic, terms are subject to change.

Greece – In Greece, while public opinion is important, it has not been the key factor in policymakers’ decisions in response to the pandemic. The newly elected legislature was only seven months into its four-year term when being expected to respond to COVID-19, indicating that the majority party in office was likely to still have a higher margin of public approval while responding to the pandemic as opposed to a legislature that has been in office for three years out of a four-year term. Furthermore, in response to COVID-19, the government has not only tackled the pandemic but the opinions and thoughts surrounding it. Not only is there is a daily address in regards to the pandemic in Greece, but following it there an address made by the Undersecretary of Civil Protection and Crisis Management, Nikos Chardalias, who clearly links policies to scientific evidence, clearly demonstrating the purpose and importance of the policies that the legislature is enacting as seen in Figure 8 (Ladi 2020).

By clearly demonstrating for the people of Greece why specific scientific procedures are being implemented, Greece has not only maintained the trust of its people, but grown it, and encouraged confidence in their decisions as a whole. There is growing confidence in their education and health systems, and the general public approval has encouraged policymakers to continue relying on scientific evidence in their decisions (Ladi 2020). Overall indicating the primary reliance on science when it comes to policymaker’s decisions and the public approval that follows when their decisions, which relied on scientific evidence, prove effective during the pandemic.

The United Kingdom – Due to the COVID-19 pandemic’s presence in nearly all aspects of life, policymakers have to create policies that take into account various sectors (health, economic, social, educational, etc.). Subsequently, policymakers are taking into account the thoughts of a variety of different groups. Two of the most influential voices during the pandemic have been the public and scientists. Public opinion holds political weight as it can be translated into votes during the next general election set to take place in 2024. During the pandemic, United Kingdom citizens were surveyed on their perception of Johnson’s benevolence, openness, and competence. Obviously, scientists and experts provide the most knowledgeable and up to date information on the best way to slow the virus’s spread. As much as the experts can help find the solution to the pandemic, they can also become a scapegoat for government officials if their strategy does not work as anticipated. As a result, the extent to which the Prime Minister and Parliament listen to the experts is not completely at the expense of the public’s trust and perception.

Based on the information in the chart on the left, most people felt that Johnson genuinely wanted to improve the country’s condition and looked to experts for advice. However, very few felt that Conservative Party member Johnson cooperated with the opposing Labour Party (Jennings et al., 2020). The supposed lack of cooperation between the two parties has continued the polarization of the parties since Johnson’s election and politicized the pandemic further.

In an attempt to prevent panic amongst the public, Johnson announced plans to begin rapid testing. The tests the government purchased are meant to be conducted by professionals on symptomatic individuals. This is in contrast with Johnson’s plan for the tests to be self-administered (Mahase 2020). Although scientists support increased testing, the rushed and seemingly poorly developed plans are being used to soothe the public as they began their second lockdown. As much as science should prevail in a public health crisis, it is not completely separated from public opinion and political interests.

Recently, multiple instances of government institutions suppressing scientific findings have been made public. During the outbreak in China and the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom, the government’s experts were concerned about the impact the virus could have when it reached them.

The United Kingdom was slow to respond, and when they did, they reported overly optimistic figures and did little as a means of maintaining peace with the public (Grey, MacAskill 2020). Political leaders believed that the democratic and individual-centered culture of the United Kingdom would make citizens less inclined to follow stay at home orders or any other type of measures they felt interrupted their lives unnecessarily. Additionally, a public health report studying COVID-19’s impact on minorities was delayed until the public expressed concern. Additionally, the authors were told not to interact with the media. In another instance, a scientist employed by the government was prevented from coming forward with their findings regarding deficiencies in an antibody test due to a “difficult political landscape” (Abbasi 2020).

The intersection of politics, science, and public opinion has allowed policymakers and related officials to pick and choose what science they follow and promote to the public; this is dangerous considering the government is also not allowing its citizens to review and formulate opinions based on objective findings. Since the United Kingdom has been the first country to approve a vaccine and has begun to administer it, it will be interesting to see how the interaction between scientists and public opinion will influence how many people receive the vaccine.

Sweden – For a scientific-minded society, Sweden’s approach to the coronavirus pandemic has been remarkably unscientific. Swedish officials claim that studies of lockdowns and masks being beneficial in curbing the spread of the virus are too early to be considered conclusive. However, the coronavirus is a time-sensitive topic, and we cannot wait the years that it takes to properly confirm a hypothesis to act; Sweden’s growing number of cases and deaths shows this. Despite what government officials claim, it is not a distrust in the science that prevents Sweden from following W.H.O. recommended procedures, such as lockdowns and masks. Rather, it is a need to prioritize public opinion over science. The Swedish government, as we’ve explored, stands on unstable ground. The balance of party alliances in the Riksdag is delicate, and one poorly planned policy initiative could send the already teetering alliance to the ground. This means that Stefan Lofven, the Prime Minister and the head of the Social Democrats, must be very careful when it comes to matters of public opinion. Personal liberty is universally important in Sweden and is prioritized by the public above the pandemic “even among the elderly” (Wengström, 2020). Directly challenging this deeply held public value would increase pressure and negative press on an already struggling government.

A vote of no confidence, which would remove the Prime Minister from office, can be initiated at any time in the Riksdag. The seats are so deeply fragmented between parties that it is very conceivable that such a vote could be successful. Further, the central right “Alliance” of parties has maintained a strong foothold in the Riksdag and is actively searching for an excuse to remove the Social Democrats from their active position in government and take over the Riksdag with a coalition of their own. The 2018 election gave only a single seat advantage to the Social Democrats, after all (Anderson 2019). The tension between the left and right wings of the Riksdag is palpable, and must always be kept in consideration when determining policy. Sweden is thus viewing the pandemic from a political standpoint rather than a scientific one. Lofven sees no other choice if he wishes to remain in power. However, this approach to the pandemic has been wildly unsuccessful, and Sweden’s rising case and death rates clearly demonstrate this.

Conclusion

Trust, then, plays an important role in COVID-19 strategies throughout the world. It allows governments and citizens to cooperate in the face of the pandemic, ensuring that policies will be followed and that governments will do their best to protect their citizens. In the absence of trust, policies intended to protect fall flat. Suppose citizens believe their liberties and rights are being restricted by the government, rather than trusting the government is acting in their best interests. In that case, they will not be as eager to follow any guidelines set forth.

As we saw in the cases of Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Greece, pre-existing states of trust in government influenced each country’s respective coronavirus policy’s success and failure. Sweden’s electoral tensions and lack of scientific basis in their recommendations led to a decrease in mutual trust and an ultimate failure to effectively combat the pandemic. In the United Kingdom, an initial misstep in the pandemic strategy, aiming for herd immunity, has resulted in a plummeting level of trust in government and hesitance to follow the nation’s newest lockdown policies. Finally, in Greece, a change in the party controlling government allowed a historically untrusted country to take great positive strides both in terms of mutual trust between the government and the governed, as well as in the nation’s successful approach to COVID-19.

The levels of mutual trust in these three countries demonstrate a trend; populations who trust their government officials will strictly follow guidelines. Assuming these guidelines are scientifically grounded, the government’s COVID-19 strategy will thus be more effective. This general trend rings true for matters outside the pandemic as well. Any policy presented by a scorned and distrusted government will be met with resistance. Policies set forth by trusted governments, meanwhile, are met much more receptively. It is important then, not only in terms of the pandemic but also to ensure orderly national conduct, that governments work to secure the populations’ trust over which they govern.

References

Abbasi, Kamran. 2020. “Covid-19: Politicisation, ‘Corruption,’ and Suppression of Science.” The BMJ, November 13, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4425.

Anderson, Christina. 2019. “Sweden Forms a Government After 133 Days, but It’s a Shaky One.” New York Times, January, 18, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/18/world/europe/sweden-government.html.

Bjorklund, Kelly, and Andrew Ewing. “Why the Swedish Model for Fighting COVID-19 Is a Disaster.” Time, Time, 14 Oct. 2020, https://www.time.com/5899432/sweden-coronovirus-disaster/.

Braithwaite, Sharon and Reynolds, Emma. 2020. “Coronavirus Cases Fell by Roughly 30% During England’s Lockdown.” CNN, November 30, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/11/30/uk/coronavirus-england-lockdown-uk-gbr-intl/index.html.

Edwards, Catherine. 2020. “Who’s actually responsible for Sweden’s coronavirus strategy?” The Local, March 30, 2020. https://www.thelocal.se/20200330/whos-actually-in-charge-of-swedens-coronavirus-strategy.

Fouda, Ayman, Nader Mahmoudi, Naomi Moy, Francesco Paolucci. 2020. “The COVID-19 pandemic in Greece, Iceland, New Zealand, and Singapore: Health policies and lessons learned.” Health Policy and Technology, 9(3): 510-524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.015.

Grey, Stephen and MacAskill, Andrew. 2020. “Special Report: Johnson listened to his scientists about coronavirus – but they were slow to sound the alarm.” Reuters, April 7, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-britain-path-speci/special-report-johnson-listened-to-his-scientists-about-coronavirus-but-they-were-slow-to-sound-the-alarm-idUSKBN21P1VF.

Halikiopoulou, Daphne. 2019. “2019 Greek elections: Hope or caution?” Party Systems and Governments Observatory, July 12, 2019. https://whogoverns.eu/2019-greek-elections-hope-or-caution/.

Horton, Richard. 2020. “Offline: COVID-19 – a Reckoning.” The Lancet, March 21, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30669-3.

Independent. 2020. “From Corbyn to Cummings: Which High-profile Figures Who Have Breached Covid Restrictions?” October 2, 2020. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/coronavirus-lockdown-rules-dominic-cummings-robert-jenrick-stephen-kinnock-stanley-johnson-b745344.html.

Jennings, Valgarðsson, Stoker, Devine, Gaskell, and Evans, Mark. 2020. Political Trust and the COVID-19 Crisis: Pushing Populism to the Backburner? A Study of Public Opinion in Australia, Italy, the UK, and the USA. Democracy 2025, August 2020. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2020-08/covid_and_trust.pdf.

Kirka, Danica. 2020. “UK’s COVID-19 Strategy Unraveling as Regions Choose Own Path.” AP News, October 14, 2020. https://apnews.com/article/virus-outbreak-england-united-kingdom-europe-northern-ireland-092b3625aabc3188791b6eec89c3e04a.

Ladi, Stella. 2020. “Regaining Trust: Tackling the coronavirus in Greece.” London School of Economics, April 13, 2020. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/greeceatlse/2020/04/13/regaining-trust-tackling-the-corona-virus-in-greece/.

Landler, Mark and Castle, Stephen. 2020. “Boris Johnson Contracts Coronavirus, Rattling Top Ranks of U.K. Government.” New York Times, March 27, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/27/world/europe/boris-johnson-coronavirus.html.

Mahase, Elizabeth. 2020. “Covid-19: Experts question evidence behind prime minister’s promise of rapid tests.” The BMJ, November 2, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4254.

McCormick, John, Rod Hauge, and Martin Harrop. 2019. Comparative Government and Politics. Macmillan International Higher Education.

McGee, Luke. 2020. “The United Kingdom’s Four Countries Take a Divided Approach to Coronavirus Crisis.” CNN, May 14, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/14/uk/united-kingdom-divided-approach-coronavirus-intl-gbr/index.html.

Moris, Dimitrios, Dimitrios Schizas. 2020. “Lockdown During COVID-19: The Greek Success.” in vivo, 34(3): 1695-1699. 10.21873/invivo.11963.

Mueller, Benjamin. 2020. “A Lockdown With Loopholes: England Faces New Virus Restrictions.” New York Times, November 13, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/05/world/europe/britain-coronavirus-lockdown.html.

Orthodox Times. 2020. “Greek Civil Protection Deputy Min: Use of face mask is obligatory in all places of worship from August 1.” Orthodox Times, July 31, 2020. https://orthodoxtimes.com/greek-civil-protection-deputy-min-use-of-face-mask-is-obligatory-in-all-places-of-worship/.

Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban, Max Roser. 2016. “Trust.” Our World in Data, Accessed December 13, 2020. https://ourworldindata.org/trust#citation.

POLITICO. 2019a. “Greece – 2019 general election results.” Accessed December 14, 2020. https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/greece/.

POLITICO. 2019b. “Sweden – National Parliament Voting Intention.” https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/sweden/.

Ritchie, Hannah, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Diana Beltekian, Edouard Mathieu, Joe Hassell, Bobbie Macdonalnd, Charlie Giattino, Max Roser. 2020. “Mortality Risk of COVID-19.” Our World in Data, Accessed December 14, 2020. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-deaths?country=GRC~GBR~SWE.

Rose, Richard. 2020. “A New Prime Minister Meets Old Constraints.” How Referendums Challenge European Democracy: Brexit and Beyond: 209-224. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44117-3_12.

The Local. 2020a. “Explained: Who are Sweden’s party leaders and what do they want?” August 26, 2020. https://www.thelocal.se/20200709/what-you-need-to-know-about-swedens-political-party-leaders.

The Local. 2020b. “Trust in Sweden’s Government Coronavirus Response Declining, Poll Shows.” September 3, 2020. https://www.thelocal.se/20200903/trust-in-swedens-coronavirus-response-starting-to-fall-poll-shows.

Trägårdh, Lars and Özkırımlı, Umut. 2020. “Why might Sweden’s Covid-19 policy work? Trust between citizens and state.” The Guardian, April, 21, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/commentisfree/2020/apr/21/sweden-covid-19-policy-trust-citizens-state.

Wengström, Erik. 2020. “Coronavirus: survey reveals what Swedish people really think of country’s relaxed approach.” The Conversation, April 29, 2020. https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-survey-reveals-what-swedish-people-really-think-of-countrys-relaxed-approach-137275.

World Values Survey. 2020. “World Values Survey Wave 7: 2017-2020.” Accessed November 13, 2020. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSOnline.jsp.

Contributors

Catherine Piro is a Political Science major with an expected graduation date of December 2023.

Carley Salerno is a Political Science major with an expected graduation date in May 2024.

Nicole Kemmett is a Political Science major with an expected graduation date in May 2024.