As the bodies piled up, it became increasingly clear that Western European powers had utterly failed to address the COVID-19 pandemic in a timely fashion.

There are many factors that come into play in regard to their mishandling, but we argue that the number one reason that Western European nations, including Italy, Ireland, and Spain, have failed to address the pandemic is the political fragmentation present in their parliamentary systems of government. The state of a country’s government directly reflects their ability to control outbreaks and the safety of their citizens.

Italy

Infamous for its political fragmentation and instability, Italy has had sixty-one governments since the end of World War II, including thirteen different prime ministers in the last thirty years. Italy’s multiparty system has led to short-lived coalition governments, which causes disarray politically, economically, and socially. After all, just last year in 2019, The Economist Intelligence Unit rated Italy as a “flawed democracy.” That being said, the spread of Covid-19 has worsened Italy’s political fragmentation. Covid-19 is devastating Italy—exposing its parliamentary system’s weaknesses.

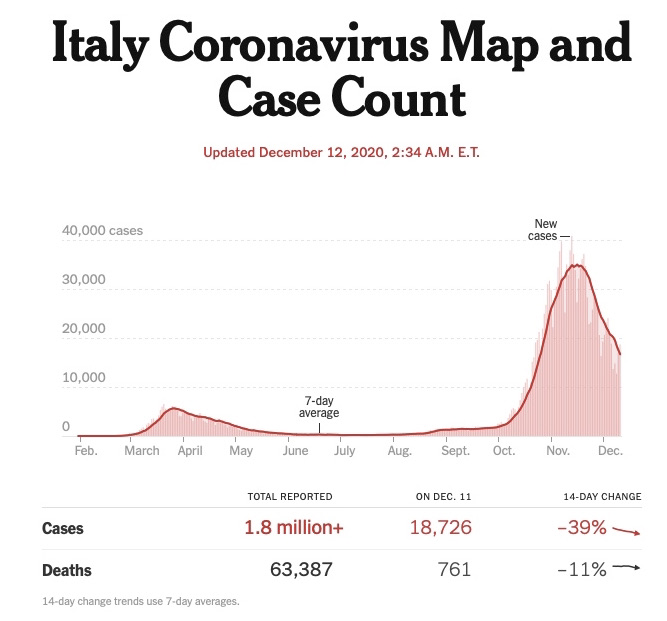

First and foremost, let’s look at the numbers. Italy has seen a total of about 1,805,800 cases of Covid-19, along with an estimate of 63,387 total deaths, if not more. Keep in mind that these numbers are subject to change as more Italian citizens lose their lives to this disease every day. In June, they saw a low of 129 new cases, but now, as of December 11, Italy has 18,726 new cases reported as the country faces a second wave. Furthermore, the head of the Italian Department of Civil Protection estimates that as we enter flu season, the numbers of new cases could potentially become ten times higher than the current numbers. So, what does this have to do with Italy’s Parliament, you may ask? The inability to effectively lower these numbers directly reflects the capabilities of Italy’s parliamentary system of government. Strong, centralized, and organized governments successfully handle Covid-19 by undergoing both short and long term action. Italy’s Parliament, on the other hand, has, and still is, only worried about the short-term.

Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte declared a state of emergency on January 31 as well as implementing a national lockdown in March, making Italy the first western country to do so. The lockdown controlled the spread quickly, in the short-term, and allowed for Italy to open back up for the summer with a set of restrictions in place. Wearing masks, social distancing, and a 10 pm curfew are a few examples of this. Although these measures taken by the Italian Parliament were both quick and effective, my point here is that they only work in the short-term. Parliament continues to fail to address the long-term consequences of this pandemic. These short-term measures are devastating the Italian economy, for example, and the government is incapable of protecting its citizens from falling into poverty.

Jason Horowitz, a writer for The New York Times, said it best when he wrote, “the coronavirus has been the great revealer of the weaknesses of governments, systems and societies everywhere it goes across the world.” For Italy, the coronavirus exposed the country’s deepest problem—the economic and social inequality that exists between the north and south. A problem that Parliament has failed time and time again to address. Do you see the common trend here? Healthcare is a huge indicator of the disparities between northern and southern Italy. Due to poor management, political patronage, and the influence of groups of organized crime, southern Italy falls short compared to the north in regards to healthcare. Even before the pandemic started, hospitals in the south were in severe debt—and now, it’s even worse. Furthermore, it is known that southern Italian businesses use off-the-books workers, making up a “street economy,” as Luca Bianchi, director of association for industry development in southern Italy calls it. However, when the lockdowns were implemented, those workers were hit hardest because they had no access to government relief packages such as stimulus checks—rendering hundreds of people helpless at the fault of the Italian Parliament.

Ireland

Ireland has a divided parliament facing constant conflict and disagreement. With the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the country has been crippled economically and socially, which has only furthered the failing of their political structure. Over the past several decades Ireland has been disorganized and inconsistent on their means of governance. Parliament or Oireachas is divided due to the several political parties and the power that each of them holds. The two major parties Fianna Fail and Fine Gael along with the Green party needed to form a coalition in order to govern the country because of the pandemic. This coalition excluded the Sinn Fein party because of its nationalist views and ties to the IRA. The fact that it takes three major political parties within Oireachas to be able to govern the country but also exclude another from taking part in the decision making shows how politically polarized Ireland’s parliament is.

The agreement between the coalition is more so for politics then it truly is for the handling of the coronavirus. The main deal of the coalition is that Fine Gael and Fianna Fail will rotate the job of Prime Minister between Michael Martin and Leo Varadkar. This took weeks of negotiations, time wasted that could’ve been used solving the coronavirus and the instability it caused within the country. As cases first began to appear within Ireland, Parliament decided that there was no necessity of precautions to be taken in order to protect its citizens and stop the spread. After two weeks, with thousands of people now sick and over 100,000 jobs lost, the government finally decided that a six week long lockdown was necessary. After the negotiations were finally settled upon and Ireland was in lockdown it took several more weeks for that same coalition to agree upon a stimulus bill in order to protect Ireland’s people.

Michael Martin has now stated that he will be lifting many of the Covid-19 restrictions regarding restaurants, stores, gyms, and pubs by December 18th so that there will be a different feeling for the holiday season than has been felt all year because of the coronavirus. This liftment of precautions and restrictions shows the inconsistency within Parliament because the coalition is allowing for the rotation of Prime Ministers and Varadkar was the one who put these precautions in place to stop the spread and now Martin is lifting them way ahead of many other major European nations. The inconsistency between the two Prime Ministers is reflective of the inconsistency between the parties in the coalition. The ineffectiveness of Ireland’s Parliament to agree upon what should be done regarding keeping their people alive and providing economic relief shows the disorganization within the legislative and why there is a divided political structure present in Ireland.

Spain

The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Spain was reported on January 31st. Patient zero was a German tourist visiting the island of La Gomera (Canarias). After a month the number of confirmed cases increased to 100. Despite knowing that Covid was coming, the Spanish government initially did very little to mitigate the oncoming crisis. It took them until March 14th, when they had 7,658 active cases and 285 reported deaths for PM Sanchez to declare a State of Alarm. The State of alarm resulted in restrictions of movement, with the exception of grocery shopping, going to the pharmacy and select other places. This State of alarm was put into place about a week after Italy went into a national lockdown on March 9th. While the state of alarm was intended to mitigate exposure to the Covid 19 virus, case numbers continued to go up and Spain went into a national lockdown on March 29th when all nonessential activities and work were stopped. By April the Sanchez government was facing harsh criticism from all sides of the political perspective. International political observers would continually write headlines like “How Spain Tragically Bungled its Covid Response” and other pieces criticizing all the Spanish authorities across the board.

One of the key issues with the Spanish response is its current parliamentary makeup. The Sanchez administration hands on by a thread and only has a majority coalition by working with Pablo Iglesias of the left leaning Podemos party and the Catalonian independence party. It took too long for Sanchez to gain emergency powers to circumvent the devolved style of government associated with the Autonomous regions as well as the hostile parliamentary chamber. As Sanchez gained his extra powers, he received criticism and vitriol from both the right wing Popular Party and far right Party VOX. Both groups criticized Sanchez for closing down all nonessential activities, and dramatically pivoting from their previous positions calling for a more severe lockdown, only to pivot back to that position once more. Even on the left, Sanchez faced difficulty from Podemos because they have been attempting to use the crisis to push through some of their non Covid related political agenda. Spain essentially cost itself time and lives by not taking a national and hands on approach sooner.

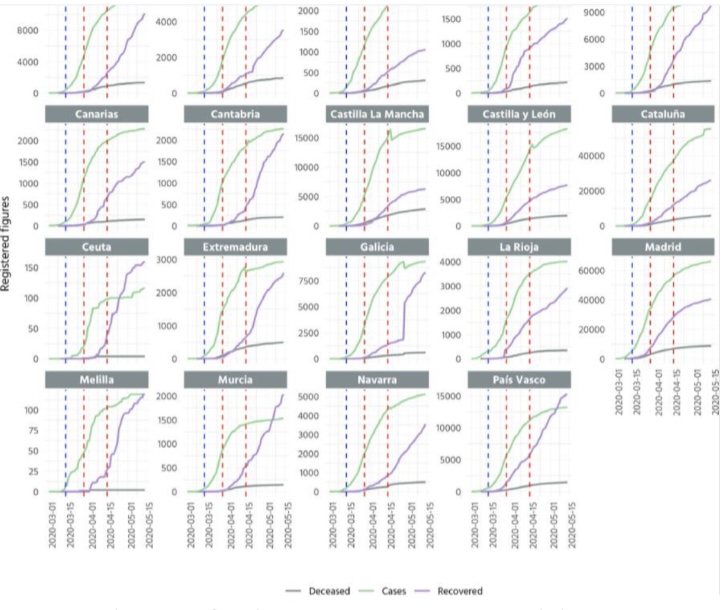

Despite intense differences in regional demographics, the Spanish Government ought to have gotten aggressively ahead of the curve once Italy started to have problems. As Figure 2 shows, Various regions of Spain experienced different infection rates. This has more to do with population demographics than regional government handling of the pandemic. That being said, the divided coalitions that comprise the Spanish parliament only furthered inaction and led to the slow response time.

Covid-19 truly is the great revealer, leaving Western European countries, including Italy, Ireland, and Spain exposed and vulnerable to its devastation. All three are suffering politically, socially, and economically at the hands of this pandemic. No one could have seen this coming, but it goes to show that these parliamentary systems of government are weak and incapable of effectively getting ahead of this virus. The instability, polarity, and disorganization of a parliamentary system are all factors that play into why these governments are helpless against Covid-19.

Contributors:

Jenna Barth is a sophomore Psychology major at SUNY Geneseo.

Connor Geraghty is a freshman Political Science major at SUNY Geneseo.

Daniel Chichester is a senior History major at SUNY Geneseo.

References

de Ghantuz Cubbe, Giovanni. “Assessing the Political Impact of Covid-19 in Italy.” EUROPP. LSE European Institute, September 29, 2020. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2020/09/29/covid-19-italian-politics/.

“EIU Democracy Index 2019.” EIU. The Economic Intelligence Unit, 2019. https://www.eiu.com/topic/democracy-index.

Ferdinando Giugliano, “Spain’s Tragedy Was All Too Predictable,” Bloomberg.com (Bloomberg), accessed December 14, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-04-06/how-spain-tragically-bungled-its-coronavirus-response.

Halpin, P., & Fahy, G. (2020, November 27). Ireland to lift COVID-19 curbs ahead of many European countries. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-ireland/ireland-to-lift-covid-19-curbs-ahead-of-many-european-countries-idUSKBN2872E0

Horowitz, Jason. “For Southern Italy, the Coronavirus Becomes a War on 2 Fronts.” The New York Times. The New York Times, April 21, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/21/world/europe/italy-coronavirus-south.html.

IPU Parline. March 10, 2016. https://data.ipu.org/node/81/law-making-oversight-budget?chamber_id=13423.

“Italy Coronavirus Map and Case Count.” The New York Times. The New York Times, April 16, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/world/europe/italy-coronavirus-cases.html.

Josefa Henríquez et al., “The First Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain,” Health policy and technology (Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine. Published by Elsevier Ltd., December 2020), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7451011/.

Landler, Mark. “Ireland’s 2 Main Parties to Jointly Govern for First Time.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 15, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/15/world/europe/ireland-coalition-government.html?searchResultPosition=29.

Taylor, Adam. “Why Italian Governments so Often End in Collapse.” The Washington Post. The Washington Post, August 20, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2019/08/20/why-italian-governments-so-often-end-collapse/.

“The World Factbook: Ireland.” Central Intelligence Agency. Central Intelligence Agency, February 1, 2018. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ei.html.

“TIMELINE-How the Coronavirus Spread in Spain,” Reuters (Thomson Reuters, April 2, 2020), https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-spain-factbox/timeline-how-the-coronavirus-spread-in-spain-idUSL8N2BO4TL.